A cursory Google search yields few resources attempting to accurately define what makes a queer icon, well, iconic. And there’s a good reason for that. Whats makes a queer icon is at the same time simple and incredibly difficult to define. One one hand, its is easy to use blanket terms like “glamorous” or “camp” and to describe queer icons, but many do not explicitly fall into any specific category. Some act and sing; some are socialites or political figures; some aren’t even queer themselves. Several are declared icons posthumously while others seems to emerge pre-iconified. There is no one defining factor, rather an aura an individual must exhibit to obtain the coveted status.

For history and context, the modern archetype of a queer icon is commonly agreed upon to be the legendary Judy Garland. Due to her tumultuous ride through fame and the media, Garland is often referred to as a “tragic” figure in old Hollywood, a term often associated with icons of the time. Stars like Edith Piaf, Joan Crawford, Marilyn Monroe, and even non-actors like Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf all embodied the “tragic” lifestyles that became synonymous with the old Hollywood mystique so correspondent with queer culture. Their images of tortured female characters who suffered for their art rang a particular chord with the oppressed community that was the LGBTQ+. They found glamor and romanticism in the pain of these women, and likened it to their own. Later stars would go on to emulate this era of “suicide chic,” mostly notably Lana Del Rey. Ironically, what Judy Garland isn’t often associated with is camp. High camp icons like Mae West, Paul Lynde, Freddie Mercury, Liza Minelli, Elton John, Lady Gaga, David Bowie, and dozens more are often who are most thought of, alongside female pop stars, when discussing queer icons.

What makes so many iconic in the queer community as well is the “diva” attitude. Forces in this category like Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Barbra Streisand, Cher, Dionne Warwick, Bette Midler, Mariah Carey, Celine Dion, Beyoncé, and others exude one word: confidence. They project brashness without arrogance; they know they are head bitch in charge and that’s why we love them. There could be a whole separate piece on what makes a diva, but here we will keep it to this: the modern diva appeals to queer people because they know their worth and let everyone know it, and that kind of healthy ego is what can pull a repressed queer person out of some dark places. That is why fictional characters like the ladies of Dynasty, Desperate Housewives, and more recently Catherine O’Hara’s turn as Moira Rose on Schitt’s Creek, have struck such a huge chord with the community.

Often those who enter the queer zeitgeist are not LGBTQ+ themselves, or even make overt references to queerness in their work. The queer appeal of these artists lies in their flippancy with regards to labels, be they referring to gender, style, sexuality, or even music genre. Those in this category that have shone the brightest have often strayed to the most extreme and colorful end of the artistic spectrum; Icelandic singer Björk has never actually described any personal queerness publicly, but what has made her so emblematic of queer indie culture throughout the ’90s was the intensely personal nature of her music, the vividly erotic characters she presented herself as in her music videos (“Cocoon,” “Pagan Poetry”) despite the non-sexualized nature of her personality, and her dogged determination to express uniqueness. Her infamous swan dress at the 2001 Oscars only cemented her status. David Bowie took a similar approach through his career by shifting characters with every album, dawning androgynous outfits for every music video, and generally not speaking of his ambiguous LGBTQ status. The spectacle was his sexual nature, not his sexuality.

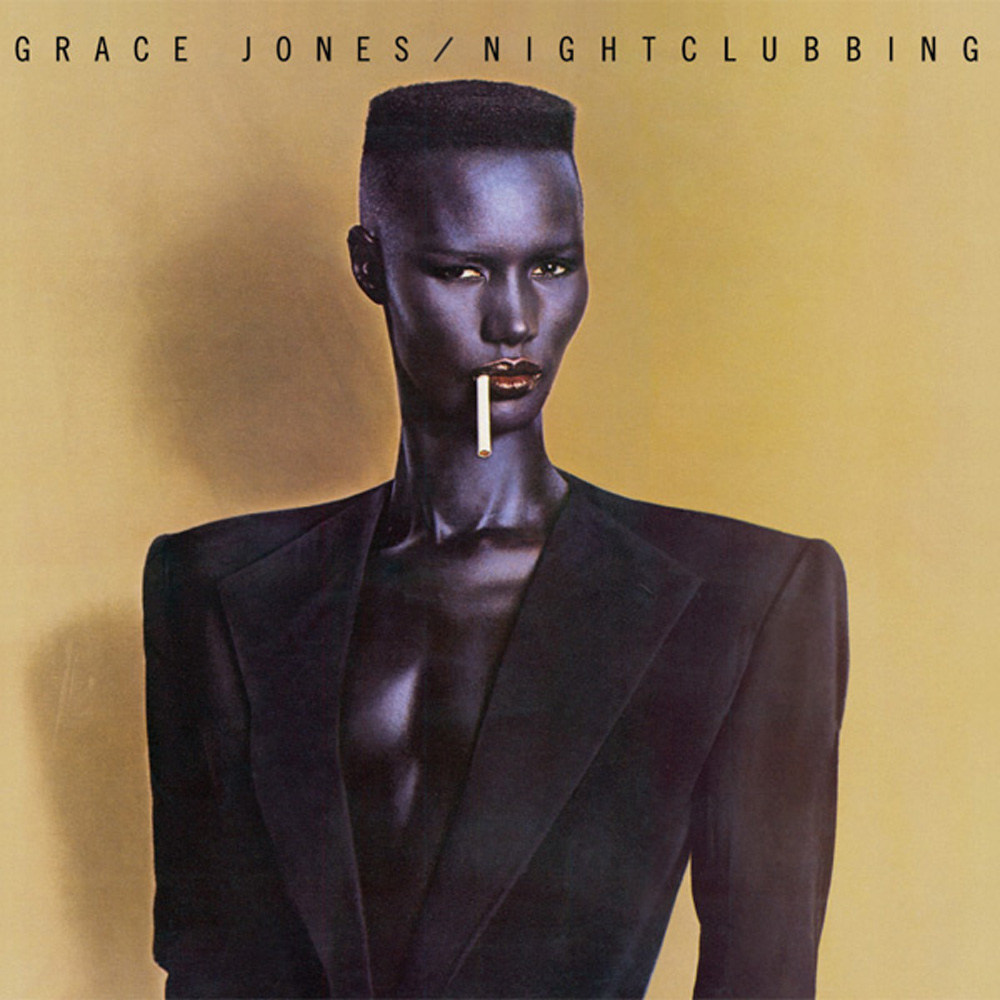

Similarly, androgyny played a unique role in the shaping of many queer icons. The androgyny movement saw such pioneers as Twiggy, Annie Lennox, Grace Jones and Boy George who all made a career out of ambiguity and refusal to fall into any one category of fashion or gender expression. This movement in some ways was a progenitor in modern culture to non-binary icons, which is why we must differentiate between “gay” icon and “queer” icon, for inclusivity. A few of these personalities include Arca, Angel Haze, and a number of popular drag performers. And, in more recent times we have finally as a society begun to collectively embrace transgender icons like Laverne Cox, Chaz Bono, MJ Rodriguez, Indya Moore, Candis Cayne, and so many others.

This doesn’t even touch upon more modern Gen-Z icons like Ariana Grande, Hayley Kiyoko, Troye Sivan, Lil Nas X and Orville Peck, and their associated trends. What sets these current-day artists apart is almost the diametric opposite to what made queerness in music and pop culture so taboo in generations past. Whereas 20th Century queer music icons put queerness first by way of overtly flamboyant imagery and subtextual lyrics, many queer and queer-adjacent artists of today hold nothing back lyrically while keeping imagery more subdued. This is not to say these artists utilize less erotica in music videos and costuming (quite the opposite), but more so that the imagery associated with their brands are far more cultivated and nuanced in execution; a more arthouse approach if you will. Like any emerging trend in queer icon-ness, this is not universal, and some artists have made entire brands around leaving nothing to the imagination (just watch Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s new music video for “WAP”).

This has all led to the somewhat recent trend of retroactive queerness in media, particularly animation. Because of their predominately kid-friendly nature, most cartoons strayed away from overt queerness. Even when utilized it was typically not in the most flattering light (Exhibit A: the now-infamous “Buffalo Gals” episode of Cartoon Network’s Cow and Chicken). Now, the creators of even the most family friendly programs like SpongeBob SquarePants have revealed the queer intent behind their character’s conception. Velma Dinkley from the Scooby-Doo franchise was confirmed to be canonically gay, as were popular side characters Mr. Simmons and Eugene Horowitz on Nickelodeon’s Hey Arnold! Characters like these have even been given entire coming out plot lines on their respective shows, like The Simpsons’ Waylon Smithers and the now-famous Mr. Ratburn wedding episode of Arthur (though the former was not received all that well). Is there something to be said about retroactively declaring a character queer in the hopes of disingenuously appealing to more queer audiences? Perhaps (ahem… J. K. Rowling), but at the end of the day these developments have been a force for good representation, and serve as important stepping stones.

Best of all, queerness is now often worked directly into the narrative of several children’s shows, like Adventure Time and Steven Universe (created by Rebecca Sugar, herself a non-binary bisexual icon), as well as the recent She-Ra and the Princess of Power. Even Bob Belcher’s subtle bisexuality on Bob’s Burgers has added him to this club.

In truth this barely scratches the surface of the supposed criterion that compose the queer icon; if anything it might confuse you even more. This doesn’t even go in depth into lesbian icons like James Dean, niche icons like Tammy Faye Messner and Ina Garten, or even superstars like Britney Spears. In actuality, what makes a queer icon is not necessarily a persona or appearance, but the emotion an individual projects. One does not profess themselves a queer icon, it is something that over time becomes embedded in the culture surrounding their output. Any individual centering their actions around wanting to appeal to the LGBTQ+ community is setting themselves up for failure (artists like Katy Perry have certainly backfired in this area). What matters is the message of their craft and personality: if that message resonates, be it camp, inclusivity, glamor, aloofness, drama, or even pain, then so too will the queer community flock.

If the sudden gay icon status of The Babadook has taught us anything, it is that a queer icon’s appeal lies in subtlety and what one represents, rather than explicit actions. What makes someone so representative of queer culture lies not in what they do, but in the culture that surrounds their art. In the golden age of Hollywood queerness was repressed, so the tragic figures like Judy Garland were made martyrs, the AIDS crisis of the ‘80s and ’90s that vilified homosexuals in the eyes of many conservative Americans led the way for stars who supported gay rights like Cyndi Lauper to command queer attention. The emergence of more queer media in the mid-to-late ’90 allowed for more powerful, no-nonsense women of pop and rock, like Alanis Morissette, Madonna, Shirley Manson and Tori Amos, to take on icon status. Boy band fanboys speculated over the sexualities of Lance Bass and Ricky Martin in the 2000’s, and by the 2010’s, queer culture was all about the loud, over-the-top, bombastically camp antics of stars like Lady Gaga and every internet sensation who was ready for their 15 minutes. There is no way to know who or what the next generation will embrace until the next big thing rolls in, but if future accelerates in the way it has recently, drag culture is sure to be the defining queer trend of Gen-Z.