Lana Del Rey has nothing left to prove. For a long time, such a weighty statement would’ve been met with raised eyebrows. But in the 11 years since Born to Die, the once-in-a-generation debut that kickstarted popular music’s sad-girl introspection renaissance, the artist born Elizabeth Grant has both doubled down on her enigmatic vision and expanded it. At the same time, efforts by naysayers and the chronically online to find holes in her “persona” continued until 2019 – that year, the release of Norman Fucking Rockwell! blew the Lana Del Rey narrative to pieces. Gone were the attempts to dig up something in the artist’s still-mysterious past to implicate her as something made-up; a character fabricated by hyperbolic fascinations with existential despair and caustic romance. Instead, publications joined all-time music legends like Bruce Springsteen in hailing Del Rey as “one of America’s greatest living songwriters.”

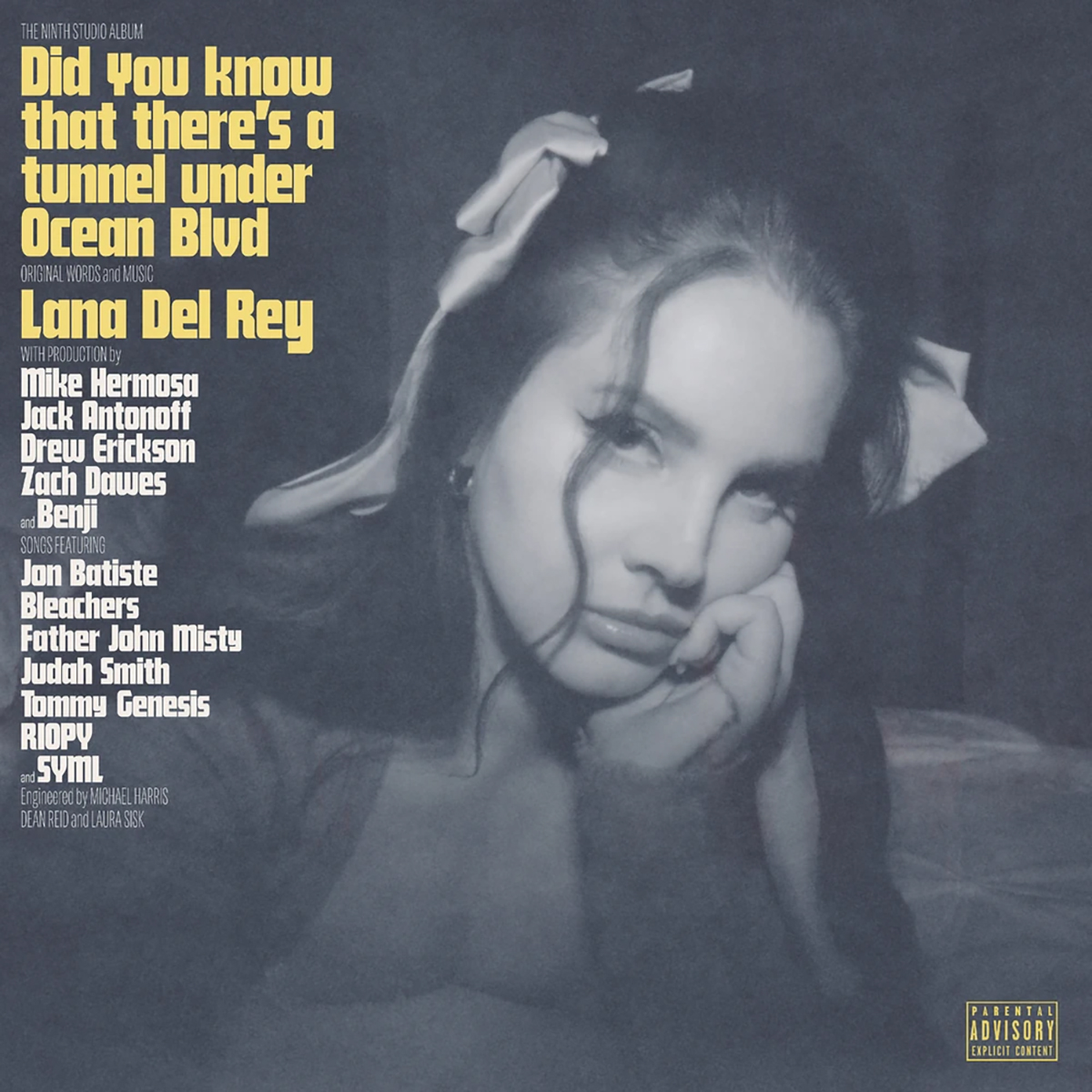

In her case, such praise comes well-earned. Nine albums in, we’ve arrived at Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd, a sprawling, 77-minute opus with a scale so large it periodically feels like the soundtrack to a lost film out of Hollywood’s Golden Age. “[Lana has] reached a point in her work… where there’s really no place to go but out into the fucking wilderness, artistically,” super-producer Jack Antonoff recently said to Rolling Stone UK. Rather than reveling in past glories – Antonoff previously served as executive producer of both NFR! and 2021’s Chemtrails Over the Country Club – Ocean Blvd takes the psychedelic and folk elements of each and subverts them into something entirely new.

The result is Del Rey’s most uncompromising project to date; a 16-song lyrical and sonic roller coaster pulled together by her ethereal croon and an introspectiveness so sharp it feels reductive to call it anything short of philosophic. Its diaristic candidness is kin to that of Blue Banisters, but here her pen reaches even more disarming heights. “Caroline, what kind of mother was she to say I’d end up in an institution?” she asks her sister, Chuck Grant, over muted piano and strings on the structureless ‘Fingertips.’ Earlier, “Will the baby be alright / Will I have one of mine / Can I handle it even if I do?”

Family has a big stake in Ocean Blvd from the start. Opening track ‘The Grants’ is a gospel-tinged ode to sacred familial memories. Later, gut-wrenching highlight ‘Kintsugi’ uses the Japanese practice of mending broken pottery with gold as a metaphor for repairing her own broken heart as she stands at her dying grandfather’s bedside. She revisits him on ‘Grandfather please stand on the shoulders of my father while he’s deep-sea fishing,’ which comes complete with the brand of excessive title that few artists can get away with. But this is Lana Del Rey, and by the time she actually sings the line, her melodic prowess immediately and effortlessly justifies it.

Elsewhere, her trademark ruminations on romantic love represent, ironically, some of the album’s most unpredictable moments. The raspy, anguished horror-folk of ‘A&W’ eventually gives way to wobbling bass and distorted moans before a trip-hop beat crashes in with Del Rey snarling, “Your mom called, I told her you’re fuckin’ up big time.” Another bait-and-switch, ‘Fishtail’ gives the impression of the album’s other piano-driven ballads, only to erupt in a thundering beat drop and computerized wails. ‘Peppers,’ a reverb-drowned psych rock cut, somehow manages to make a sample from Canadian rapper Tommy Genesis work as its chorus.

Across wandering ballads, a roster of guest features (including Father John Misty and Bleachers, Antonoff’s own band), and even a four-minute iPhone recording of a sermon from celebrity pastor Judah Smith set to a piano melody that’s almost gothic, this is an unfiltered Lana like never before. When taken as a whole, this is a towering, existential reflection – and yet Del Rey comes off more realized than ever. “I’m a different kind of woman,” goes ‘Sweet.’ “If you want some basic bitch, go to the Beverly Center and find her.” It’s one of many statements that throws a wink in the direction of those who have misunderstood her. At the same time, these humorously pointed jabs confirm what the artist’s legions of diehards already knew: Lana Del Rey has been telling us who she is from the very beginning, many just weren’t listening.

This is not to say that she has fully arrived. The acquisition of knowledge – of experience, of self-realization – inevitably brings about bigger questions, and Lana Del Rey knows this. Rarely, if ever, is she claiming to have the answers. Instead, Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd is a demanding excavation of some of life’s biggest, weirdest, and saddest mysteries, and rarely has the journey ever sounded so beautiful.