The Untitled Magazine had the opportunity to travel to Montreal, Canada to visit the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and attend the gala opening of Focus: Perfection Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition. Editor-in-chief Indira Cesarine sat down for a one-on-one with the museum’s director and chief curator, Nathalie Bondil, who since taking the helm in 2007 has distinguished the museum as not only the most visited museum in Canada, but firmly positioned it as an internationally renowned voice for arts and culture. The innovative program of exhibitions she has initiated have included introducing fashion exhibitions, such as the “The Fashion World Of Jean Paul Gaultier From The Sidewalk To The Catwalk” which has since toured to 12 cities and been viewed by over 2 million visitors, as well as music exhibitions, such as “Imagine (Yoko Ono and John Lennon)” and “We Want Miles“. She has dramatically expanded the museum to include several new buildings, as well as converted a church into a 462-seat concert hall which presents over 200 performances a year. She has introduced educational programs and art therapy as well as oversaw the restoration of over 4000 works from the museum’s collection. It is not surprising that she has also been the recipient of several honorable distinctions, including her appointment as a Member of the Order of Canada for her contributions to the promotion of the arts and culture.

Read the full interview below for more about Nathalie Bondil’s visionary curatorial and the latest exhibits that have put the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts on the map.

Indira Cesarine: You’ve made a huge impact on the art world since you’ve come on board as the director of the museum. You’re the first female director and also the first to bring fashion exhibits to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Can you talk about your decision to bring fashion to the museum?

Nathalie Bondil: I am an art historian so I’m used to seeing pictures and sculptures but when I saw haute couture for the first time I was really amazed by the quality of what I saw. I think it’s easier to see a Van Gogh or Monet than it is to see an haute couture dress. Not many people have the opportunity to see haute couture in person. In a museum you want to show great works of art that are not normally accessible and to me, haute couture is one of the most exclusive fields you can ever think about. It’s not enough to see fashion photos, even if they are by great photographers, you need to see the works in a close way if you want to understand the price and why it is called “haute couture.” I am lucky enough to be invited to fashion shows sometimes but it’s very quick. They work so hard and then it’s a few minutes and goodbye! You don’t have the time so see how it’s made so it’s not really fair, if you want to explain the extreme quality and the excellency of the job. I remember when I saw the first corset with embroidery made by Lesage, of course. I said ‘Oh my god, it’s madness!’ In fact, haute couture is madness. You just want to give to the people the opportunity to see it in a close way, not on the catwalk. I don’t think that people normally understand the subtlety of it. It’s easier to see Rodin, Van Gogh, Vermeer – you just buy your ticket and go to the Met but if you want to see an haute couture dress you cannot see it in many museums because they are very fragile so it’s truly a privilege and an opportunity to be able to make such an exhibition. The priority for me was not just the excellency of the haute couture but also the fact that for me I do not care if one artist will express themselves through cinema, couture, fashion, or painting, they are just tools. Either you have a great artist with a great imagination – or not, that’s all.

IC: Yves Saint Laurent was the first of the fashion exhibitions at the museum, you mentioned that he died the day of the opening?

NB: Maybe one or two days after but it was within the opening week. We knew that he was very ill because we worked with Pierre Bergé and with a team who knew Yves Saint Laurent from the very beginning. The whole historical team was there. The exhibition became a kind of memorial, it was the first retrospective, it was really moving. Yves Saint Laurent is so important in the imagination of all kinds of generations because he gave power to women. It was something you cannot forget.

IC: The Jean Paul Gaultier exhibit has traveled to twelve cities and it’s ending with a celebration. Where is it going next?

NB: It’s the Jean Paul Gaultier road show! After seven years, it’s coming back to Montreal. There will be a kind of celebration wedding cake and the theme will be “love is love.” In Montreal it will be a great event because this city is so open minded. The party will be devoted to the wedding dress but for man or for woman or together, man and man, woman and woman, all kind, everything, mixed! So that will be the final celebration.

IC: Is this going to be a new selection of pieces?

NB: Yes, absolutely. There will also be a new book, with Thierry-Maxime Loriot who is in Paris right now. He has very good ideas for a new series of pictures which have never been displayed that we are working on for the exhibition.

IC: Are there other designers that you would like to work with?

NB: Yes, yes, yes!

IC: Was it hard to adapt fashion to the museum environment?

NB: The Jean Paul Gaultier exhibition was very special because we had animated mannequins which was a completely brand new technology. I remember talking with Pierre Bergé and asking what kind of mannequins he wanted for his costumes because it’s very important when you don’t have live models. For Pierre Bergé it was iconic style, white model statues. When I asked Jean Paul how he envisioned the mannequins he said, ‘Well I would like to pay tribute to living people, to the people I love.’ You know he was the first one to introduce wide casting. In France, it was not the first for black mannequins, because Yves Saint Laurent was the first, but for Arabic type mannequins with varied eyes, and all kind of unusual profiles he was the first. People love Jean Paul Gaultier because he is for fat people, old people, everybody! Everybody can have fun in their body. It’s very inclusive. We adapted the fashion and technology completely for each venue, depending on the architecture and the floor plan. In each venue there were adaptations by Thierry Loriot. When we were in Madrid the Frida Kahlo fashion themes were more obviously displayed. In Paris it was very very special, that was a big, big scale, because we also had a moving catwalk with a mechanical system for rotation. We also recorded Catherine Deneuve describing each costume. We made a special section for the muses in London because in each city Jean Paul is so well appreciated. He has so many friends everywhere, so we paid tribute and gave special focus on those special people.

IC: You’ve also had a major impact with your musical exhibitions in the museum –“WE WANT MILES”: Miles Davis vs. Jazz, and Imagine: The Peace Ballad of John and Yoko. You also did one on Warhol. What made you decide to do these?

NB: One of my best friends, Emma, is now running the Centre Pompidou-Metz and is a specialist in music and 20th century art, so with her and other people I was really aware about the innovations in crossing music with visual art. I think that music is interesting because when you are looking at something it really captures your senses and helps you to focus on contemplating your experience. Normally you jump from one image to another so when you are a curator you say ‘How can I catch the attention of someone?’ I want them to see, not to jump, so musical immersion helps a lot. You can see in the Mapplethorpe exhibition – it’s not a musical exhibit, but I worked with a specialist who made a very sharp selection of music for the exhibition so it gives it a totally different sensation. I think that music improves your experience and your relationship to the work.

IC: Traditionally museums are meant to be silent so it’s very experimental to be introducing sound to the exhibits.

NB: There are some exhibitions which include music because music is really a part of the concept and there are other exhibitions where I will invite music. It depends on how you want to bring music into a space. When you listen to music alone you have your experience alone but when you listen to music with people you share the experience. For Yoko and John we had one room dedicated to “Imagine” so the questions were, ‘How do you make visible something invisible, How can we explain that this song is a masterpiece, even if you don’t like it?’ So there was a specialization of music, the installation was really important. Making an exhibition is like theater but the actors cannot move, they are on the walls, and instead the museum goers move. It’s a story through which you walk. It’s like if you were walking through a book. Working with music gives that another level. When you’re capturing the senses it’s better to talk to your heart or your gut before your brain. When you see something and you are moved and you are shocked, then you are interested. It’s really boring if you must read something in order to understand the intention.

IC: I understand you converted a church into a concert hall which is now known as Salle Bourgie?

NB: Yes! Thanks to a great museum donor, mister Pierre Bourgie, we had the opportunity to buy the church. We thought we could build a gallery on the back for art but what could we do with the main part? It was not feasible for art because of the conservation system and restrictions. By chance, or as you say in English – serendipity – I met Pierre Bourgie and he wanted to create a foundation for music so he said ‘Okay I will buy a church to do.’ By a miracle we got this church with amazing sound, the acoustics are really really good, and then we even improved on it, so now it’s a professional concert hall. At the beginning we thought we would have 80 concerts or maybe 100 every year but we have more than 200 every year so it’s really growing. It attracts people from music who are also interested in art and the reverse is also true. It speaks to the new place for museums. Museums are no longer just temples for art collections but really they are a place for experiencing life and living art. Art speaks many different languages.

IC: You are going to open a big pavilion that will focus on art therapy. Can you tell me about your plans for that project?

NB: It’s a simple statement: art helps you feel good. They are doing all kinds of new experiments and they understand that in fact beauty is a physiological, biological need. For humans and for animals, beauty means health in nature. Thanks to brain imaging, we know that when you have an aesthetic emotion. It animates the part of your brain that is linked to sexuality and reproduction. When you want to reproduce, you want someone healthy – you want someone beautiful. Even if you hate museums, aesthetic emotion is a part of your life. So we are making a link between the biological and the cultural by making all kinds of different programs concerning health. For example, for older or convalescent people, it’s hard to exercise in the winter because it’s very icy here and it’s not easy to walk. So we have a special tour conceived by therapists and doctors that goes from one point in the museum to another. We have also other programs which are more about accompanying the patient with the family. It’s about art therapy and how the aesthetic environment can help people and their wellbeing. It helps especially with alzheimer’s, autism, mental health, and suicide prevention etc. We have other pilot projects also with scientists lead by different institutes. Culture will be as important for our health as sport was in the 20th century. Everybody understands now that you have to get some exercise but we also want people to realize that culture will help people to feel better too. For example, we know there is an impact on post traumatic children. We worked with Syrian immigrants and of course they cannot speak about their experience but they draw. Art is not only good for your physical health but also for the collective health. Art can talk about everything.

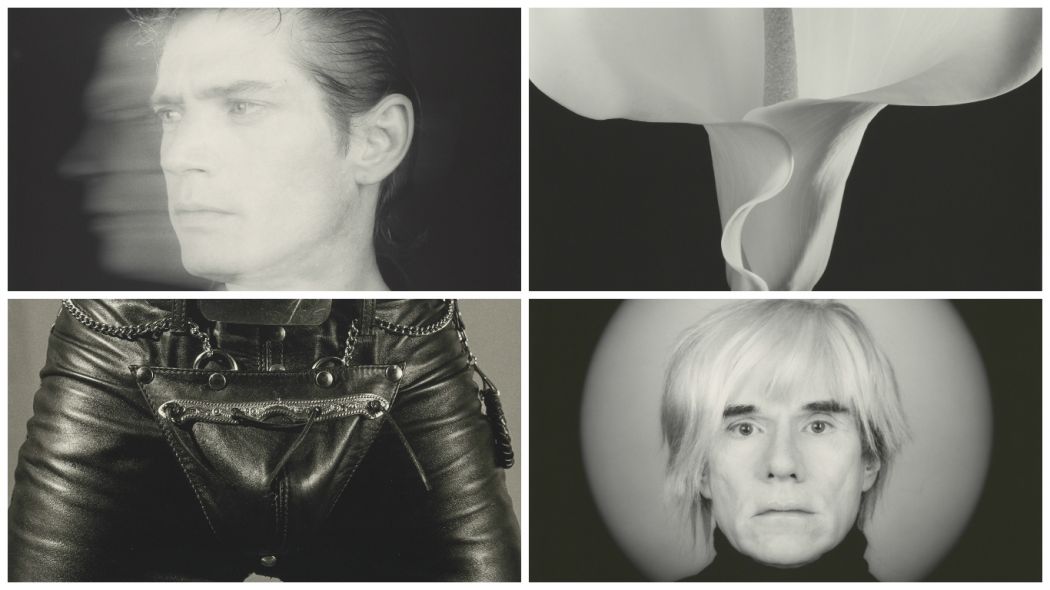

IC: I would also love to talk about the Mapplethorpe exhibit, Focus: Perfection, which is one view now at the museum through January 22, 2017. It first showed at LACMA and this is the first time it’s being shown in Canada. What was it specifically about this series of images from Mapplethorpe that you thought was important to bring to Canada?

NB: It’s the LACMA and Getty together, and we are privileged because we can present both exhibitions. From an academic point of view, this is the first time in Canada that there is a show from one of the best photographers of the century. Mapplethorpe is one who talks so directly about American taboos – violence, homosexuality, and black beauty. We still read the newspapers and see that there are still issues concerning racism and homosexuality, so it’s about inclusion. He’s a visionary. Even though he made photos and art, he didn’t want to be considered a photographer but really as an artist. His vision is unique and perfection but also sometimes so paradoxical with the composition. It’s fabulous. He’s so precise about techniques and respectful of his medium but also his art still talks a lot. It’s still so relevant and innovative now in 2016. He’s important especially now during the American election. I also wanted to have something about censorship because it’s very important when it comes to art. All of the social issues and strong values that are supported by his works are absolutely the reason why the exhibition is here today. I understand it’s not for everybody, there are some people who do not want to see pornographic or naked images and that’s okay. We are also going to have a naked visit for naturalists.

IC: So people can come to the museum naked?

NB: Yes, and the guides. Only in the Mapplethorpe exhibition.

IC: To be able to walk around a museum naked, the way you were born, adds such a unique element!

NB: Yes, and it will be very respectful of course. It will be very clean and you cannot take pictures. It’s really just about having this intimate experience with the art. There is this type of visit, but we also want grandparents and children to come at other times. When you see his work online there are lots of “hard” images, homoerotic images, but when you go through the exhibit there’s a lot of very clean images. There is a different side to his work. Also outside of the exhibition, we worked with many different organizations – LGBT associations, black rights associations, black LGBT associations, etc. We also worked with children in schools. We took some images from the collection along with some analyzations of the works and it will be included in a tour with schools. It’s about psycho emotional relation and understanding differences.

IC: How do you address some of the more controversial images, especially when it comes to younger people that might want to see the show? Are they able to access the entire exhibit?

NB: There will be warnings with suggested age restrictions. We want to respect people, it’s freedom in a museum. If you want to see you can see, if you don’t then you don’t. That’s all. We are here to give freedom, we are not here to censor, but we are also not here to impose. We always educate the cognitive intelligence but emotional intelligence is extremely important, it’s what separates us from the rabbit or the computer.

-Interview by Indira Cesarine for The Untitled Magazine