Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

September 13, 2024–January 19, 2025

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

March 9–July 6, 2025

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

August 30, 2025–January 4, 2026

Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012) was a pivotal Black woman artist of the twentieth century, though her work has not received the mainstream recognition given to many of her male contemporaries. The Brooklyn Museum, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, is addressing this oversight with the exhibition Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies. This comprehensive presentation, in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago, features over 150 works, including well-known sculptures and prints, rare paintings and drawings, and important ephemera. It is the most extensive exhibition of Catlett’s work in the United States and honors Catlett’s revolutionary spirit and radical activism.

Catlett, an avowed feminist and lifelong activist, emerged as an artist during the 1930s and 1940s, marked by significant social and economic challenges. Growing up during the Great Depression, she observed class disparities, racial violence, and U.S. imperialism, all while pursuing a modernist artistic education. For nearly a century, she used her art and activism to fight these injustices. Through organic abstraction, American and Mexican modernism, and African art influences, Catlett’s prints and sculptures center on the experiences of Black American and Mexican women, addressing issues of race, gender, and class.

Originally from Washington, DC, Catlett moved to Mexico in 1946 where she spent the remainder of her life. In Mexico, she joined the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a renowned artist collective, and became an active participant in leftist cultural circles. Despite her relocation, Catlett remained deeply connected to the Black liberation struggle in the United States, drawing inspiration from African art and artists like Barbara Hepworth and Käthe Kollwitz, merging her political activism with her artistic practice. Her art continues to resonate with those fighting against poverty, racism, and imperialism.

Elizabeth Catlett’s art is renowned for its distinctive style, marked by bold lines and both simplified and voluptuous forms that powerfully convey emotion and strength. Her sculptures and prints reflect a synthesis of traditional African art influences and modernist principles, resulting in striking visual compositions that emphasize the physical and emotional resilience of her subjects. Catlett’s work integrates these aesthetic choices with a profound commitment to social justice, addressing critical themes such as racial and gender inequality. This combination of technical mastery and deep socio-political engagement ensures that her art remains visually captivating and profoundly impactful.

The exhibition is organized chronologically and thematically, tracing Catlett’s career from her early activism against lynching in high school to her formal education at Howard University and the University of Iowa, where she became the first recipient of a master of fine arts degree. It includes her early paintings and sketches, defying the notion that she was solely a printmaker and sculptor. Catlett’s time in New York introduced her to modernist European sculpture and Popular Front politics, further shaping her artistic and political perspectives.

Accompanying the exhibition is a book that offers a detailed look at Catlett’s nearly century-long life, highlighting both overlooked works and iconic masterpieces. Edited by Smithsonian curator Dalila Scruggs and co-published with the University of Chicago Press, the book addresses various aspects of Catlett’s development as an artist-activist, the impact of her political exile, her pedagogical legacy, and the diverse influences on her work. The exhibition underscores Catlett’s enduring legacy as an artist who used her art to drive social change and empower marginalized communities.

Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies seeks to correct the historical oversight of Catlett’s contributions, presenting her as the significant and revolutionary figure she truly was. Through this comprehensive collection, viewers can appreciate her profound impact on art and activism. Read on to see the UNTITLED’s interview with Catherine Morris, curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center of Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum and a key person in the creation of this exhibition.

UNTITLED’s Katherine Olsen: What makes “Elizabeth Catlett, a Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies,” stand out from other feminist exhibitions, and then also, how is it in conversation with these works?

Catherine Morris: I have specialized in thinking about feminism as a methodology, as a method for looking, since I’ve been at the Brooklyn Museum. In the process of doing that, we’ve been very interested in thinking about the ways in which feminism is a much more expansive and broad political and social movement than the one that many of us have traditionally understood to be second-wave feminism, primarily white feminism.

So Catlett is, for me, the perfect example of a woman artist who embraced and identified herself as feminist in addition to being an activist for racial justice from her earliest years. And she was born in 1915. So before the First World War, before the first pandemic, before so many things, and she lived through the first Obama administration too.

So that’s an extraordinary span of time and that basically covers the 20th century and so she writes an entirely enriching and transformative history of feminism in the 20th century. So that’s a big deal. I don’t know that that’s a task that anybody can do in one exhibition, right? But it is very much the inspiration. Part of the inspiration for me for doing this show is really thinking about what Elizabeth Catlett’s life and work offers in terms of rewriting a history of the 20th century in relation to feminism and in relation to racial justice.

With this amazing legacy of almost a hundred years of work and with also so many people working on this exhibition: so there was a curatorial team responsible, I understand, with the Brooklyn Museum and the National Gallery of Art and also the Art Institute of Chicago, so with how many people working on this project how did it come together?

We had a conversation, [Dalila and I] had one of those, you know, before COVID, meeting in the hallway, like, “we should do this” conversation. So for us, it happened very spontaneously and very organically. From there as we started to do our research and think about how to approach the subject and present the possibility to the museum and go through the process of having the exhibition approved, we found out that the National Gallery was also working on a show.

And the curator down there, Mary Lee Corlett, who is a print specialist, soon joined forces. So the opportunity to join in partnership with the National Gallery and the Brooklyn Museum is extraordinary and amazing. And then to add to that the fact that the third venue for the exhibition will be the Art Institute of Chicago also just felt like a real alignment because those are the three cities that really define the moments in Catlett’s life where she developed as an artist and as a activist and as a person who was thinking through what art needed to do for the communities that she prioritized.

So the people involved were Mary Lee Corlett, Dalila, and myself as co-curators. Mary Lee has subsequently retired from the National Gallery. So Dalila and I have been primarily the curators on that, but we are working with the amazing curator Sarah Kelly Oehler in Chicago. We have extraordinary support at the National Gallery from Rashieda Witter.

And here also curatorial assistance. So yes, exhibitions of this type and most exhibitions, I would hazard to say, are not typically one-person operations. And in the case of Catlett, what we’re particularly interested in as well is thinking about her work, her life and her work are often kind of sliced and diced, as it were, between painting and sculpture, Mexico and the United States.

And we were very interested in bringing all of those things together in a more organic way, which is the way one’s life is lived, right? History tends to want to go back and make everything neat. Working with Mary Lee was an extraordinary experience because of her expertise in printmaking.

You talk about Chicago, New York City, Washington, D. C., and of course, Mexico. Can you just tell me a little bit more about these different eras of her life and how they impacted her art?

She was born and grew up in Washington, D. C. in a household that was primarily composed of her mother—her father died before she was born—and her grandparents. And she had two siblings.

She went through Dunbar and other important schools in Washington. Or you know, this is obviously during Jim Crow. Washington, D. C. famously remained one of the most segregated cities well into the 20th century. But she was very much a part of a local community where an early interest in art was supported, which is highly not the norm even to this day. You can imagine most of us telling our parents we want to become artists, the response we get. But then she went to Howard University right at the moment at which the real establishment of an African American art history was happening. So she found herself in a very dynamic world of artists and art historians.

She had been admitted to Carnegie, the Carnegie Institute, but she was denied entry when they found out that she was Black. She flourished in D. C. and from there worked several years as a teacher before deciding to get her master’s degree at the University of Iowa—where she worked with Grant Wood, which is an extraordinary kind of connection as well to the legacies of social realism—receiving one of the first MFAs in sculpture ever. Where she also, P.S., was not allowed to live on campus, though now there is a dorm named after her at the University of Iowa. And from there she continued teaching at Dillard in New Orleans, [and] spent a transformative summer in Chicago where she was really introduced to a real political moment [socialism] —renaissance in a way—in Black thinkers and artists at the South Side Community Center and other places. In that period of the post-depression socialism and communism were still very much part of a, a political conversation in this country, even as it was working its way towards the McCarthy era when it would be shut down.

It was a very important part of the conversation for many people in the post-depression era as we know, and that’s something that’s important because I think Catlett brings that history into the 60s and 70s. Then she spent several years in New York. Again, finding herself surrounded by and engaged with the modern art world, working at the Art Students League, meeting people like Dorothy Miller at MoMA, but also involved with Black artists and Black thinkers in both Harlem and in downtown New York, where she also taught at the Carver School, which was a socialist organization where she really, I think, learned [about] the creative drive that she saw in people across economic means.

She taught dressmaking and as she put it, learned a lot from the working-class people that she was exposed to. And that had a dramatic impact on her focus on who she wanted to communicate her art to. In Iowa, she had at Woods Encouragement really dedicated herself to a subject that she knew.

And that was Black motherhood and Black women. I can’t even imagine the extraordinary radicality of that at the time. But also in New York, she was exposed to modern art. You know, she was interested in Picasso. She famously, when she was at Dillard, rented a bus to take her students to what is now the New Orleans Museum, in a park that Black people were not allowed to get to enter. She rented a bus to take them to the front door while the museum was closed because she was determined to have her students see Picasso’s work.

You mentioned earlier that Catlett was supported in her pursuit of art from a young age. What was her early art like and how much of it will display at this exhibition? What can viewers expect thematically from these pieces? And also I understand that they might differ in medium as well.

The story is that in a class in an elementary school, Catlett carved—I’d have to double-check—I think it was an elephant into a bar of soap. And from there [Catlett] became very interested in the process of carving and art making. She entered Howard studying, initially, design with Loïs Mailou Jones, an important artist, and eventually changed to painting and fine art.

Painting is definitely part of Catlett’s story. Unfortunately, a lot of the early work is lost. We do have a couple of major wonderful figure study drawings that are in the collection of Howard that were kept from when she was a student there. That’s unusual. And also some design studies that she did when she was working with Loïs Mailou Jones.

So in that case, we will be showing her work. In terms of painting and drawing, I think that there’s a lot to be explored with Catlett’s work. We have worked very hard to get painting into the show, and that is part of the early part of her production in those years in Chicago and in New York.

This is a show that is built on very important legacies. It is not a show that the research comes out of the ether. It is a show that is very much dependent on the legacy and work of primarily HBCUs who collected Catlett’s work during her lifetime. Hampton University has one of my favorite works in the exhibition, which is a painting that [Catlett] made of an army worker, an army nurse, which to me encapsulates a kind of social realism with this image of a woman—who’s clearly got a red cross—involved in this kind of civic work. [It’s] action, but the background of the painting is urban, but it’s also very abstract. It reminds me very much of modernist painting of the period. So it’s a really wonderful example of the multiple directions, as it were, the Catlett was looking at that moment.

In her later works she’s more developed in her intersectional themes of the Black liberation struggles in the United States and the female experience in both America and Mexico. And so you’ve already mentioned some pieces, but which of these later works speak most directly to these particular movements and will any of those be on display as well?

When Catlett was barred entry to the United States because she was considered a dangerous person, she recorded an interview. The title of our show comes from the recording of that speech when she said, “Insofar as the United States government considers me a dangerous person, I am, and always will be a Black radical artist and all that it implies.” So that’s where our title comes from. And that’s important to the question you just asked because while she’s in Mexico in this period and she can’t come into the United States, she is very aware of what’s going on in the United States and very much wants to be a part of that conversation and support it in any way. She, Catlett sees herself very much as Part of a historical legacy, both people that came before her and the future generations that she wanted to support.

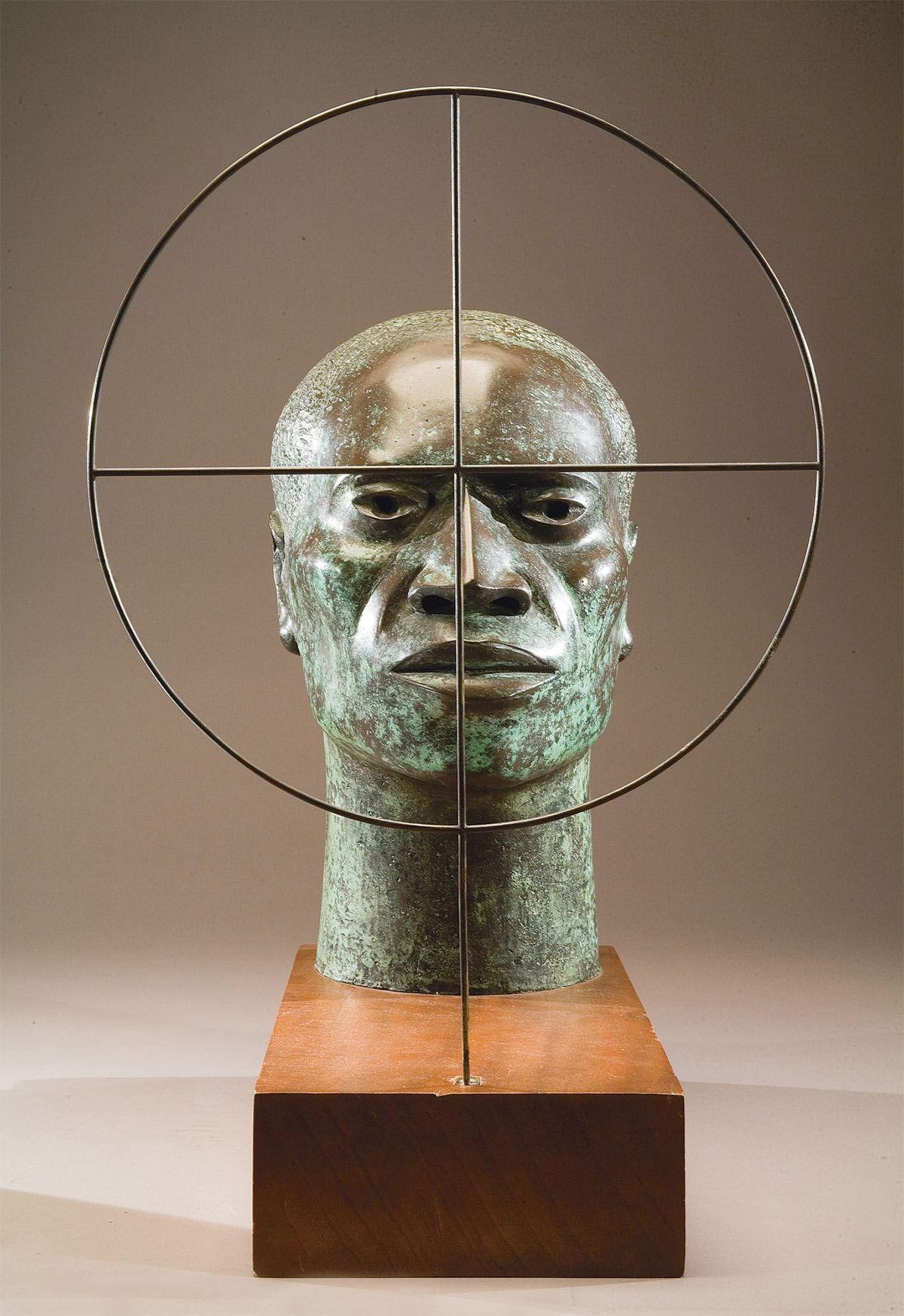

So one of the most significant works to me in that context is Homage to My Young Black Sisters, which will be in the exhibition, which we’ve shown several times at the museum before, including in We Wanted a Revolution, an exhibition that I co-curated that Catlett was part of. And that work to me really encapsulates so much of that moment in the late ‘60s where she’s seeing the power of the Black Arts Movement. She’s seeing the power of the Black Panthers and the power of the radical movement towards racial equity in this country, including the Raised Fist. Obviously, the Olympic moment of those Raised Fists happened in Mexico City, where she was at the time, so that image is very important and has interesting transnational connotations. [There are] two other important works, both of which have also been shown at the Brooklyn Museum. One is called Target, and it is a sculpture that she made—a very traditional male bronze head—that later in the ‘70s she put a rifle scope in front of to mark the death, the assassination, the killing of Black men.

We have a beautiful work we’re borrowing from the Schomburg called Political Prisoner, which is a work made in relationship to the arrest of Angela Davis. Catlett was very involved in and vocal about that situation.

The other thing I’ll mention, [is that] in her later career sculpture and printmaking are what Catlett was known for. There are lots of examples of small domestically scaled prints and sculptures by Catlett, and that was very intentional on her part, wanting to have these works be available to people to live with, to have people be able to live with art in their home, and you will run into people who grew up with a Catlett print on their wall. But one of the other ways later in life that she very actively sought to engage in her, with her Black and Mexican public, was through public art. So we are closing the exhibition with a section devoted to the very significant public artwork she made later in her career, including a wonderful bronze relief on the facade of the engineering building at Howard called Students Aspire.

And speaking of her audiences, she seems, and you’ve mentioned that she was very aware of the people that were engaging with her art and how she wanted people to engage with her art. You talk about how she tried to make her art available for people to see. How was that reflected in the themes of her art?

I think [that’s] the beauty of the theme of her art: Black women and Black mothers and children. There’s always a push-pull in all this, which is so fascinating, right? Because the female form and the female issue of mother, motherhood, are art historical subjects going back ages. I think that your point about art not being so readily available to the public is a relatively modern notion.

I think it defines modernity starting in the mid 19th century. We think about art for art’s sake and all of that. And but you’re right also with the salon, which predates that, you know, a kind of exclusivity, particularly in the West. I think that Catlett was aware of all of that.

How did this awareness of her audience and her intentionality in her audience show up in her art?

So I think it’s a combination. I think that she leaves Iowa with this dedication to this subject that is a kind of universal subject. So it’s not all that common for her to make portraits of people. She does often use people she knows as sitters, but often, typically, her work is more universal in that way that I think also relates to modernism.

But having said that, she also then goes to New York and is introduced to a real desire to engage with making art available to working-class people. That is then reinforced dramatically in Mexico at the TGP. So I think that she does come out of a very long line of historical drivers towards engaging politically with a nontraditional audience. I think that her commitment to those two things also informed her. She talked in an interview that she did with Glory Van Scott for the Hatch Billups collection about not being so interested in the commercial art world, not being so interested—this is in the 70s—in feminist art that’s emerging in New York, and [instead] being committed to, to her people. And as a result, I think institutions like the Brooklyn Museum have been well aware of Catlett, but haven’t necessarily presented her work in a historical context that aligns with the histories that we traditionally tell. And I think that’s one of the interesting things about this show.

The Brooklyn Museum, the National Gallery, and the Art Institute of Chicago need Elizabeth Catlett more than Elizabeth Catlett needs us. And I think that what that means, it’s kind of a flippant comment on one level, but on another, what I think it means is that she brings conversations that we need. They are not conversations that reinforce the status quo.

They are not conversations that re-entrench art historical stories that have been told in places like this for years. She’s aware of them and in many cases in some ways is responding to them—usually obliquely because it’s not her priority—but it’s present, and it’s fascinating to think about what that means in an installation in places like the Brooklyn Museum and the National Gallery and the Art Institute.

This brings me to my last question. What does such a large retrospective mean for Elizabeth Catlett’s legacy?

I say this all the time, but for me, the best exhibitions are not definitive. The best exhibitions invite more exhibitions. So, my hope is just that this exhibition makes more younger scholars and art historians and artists think about Catlett. And maybe understand [that] the ways in which history breaks up social movements is not the way people live their lives.

And Catlett is proof of that. You know, she lived through the 20th century in such a way that she brought so much history into the ‘60s and ‘70s and into the ‘80s and ‘90s and into the 21st century, but at the same time she was consistently a contemporary voice. And that’s the kind of art that makes me very excited.