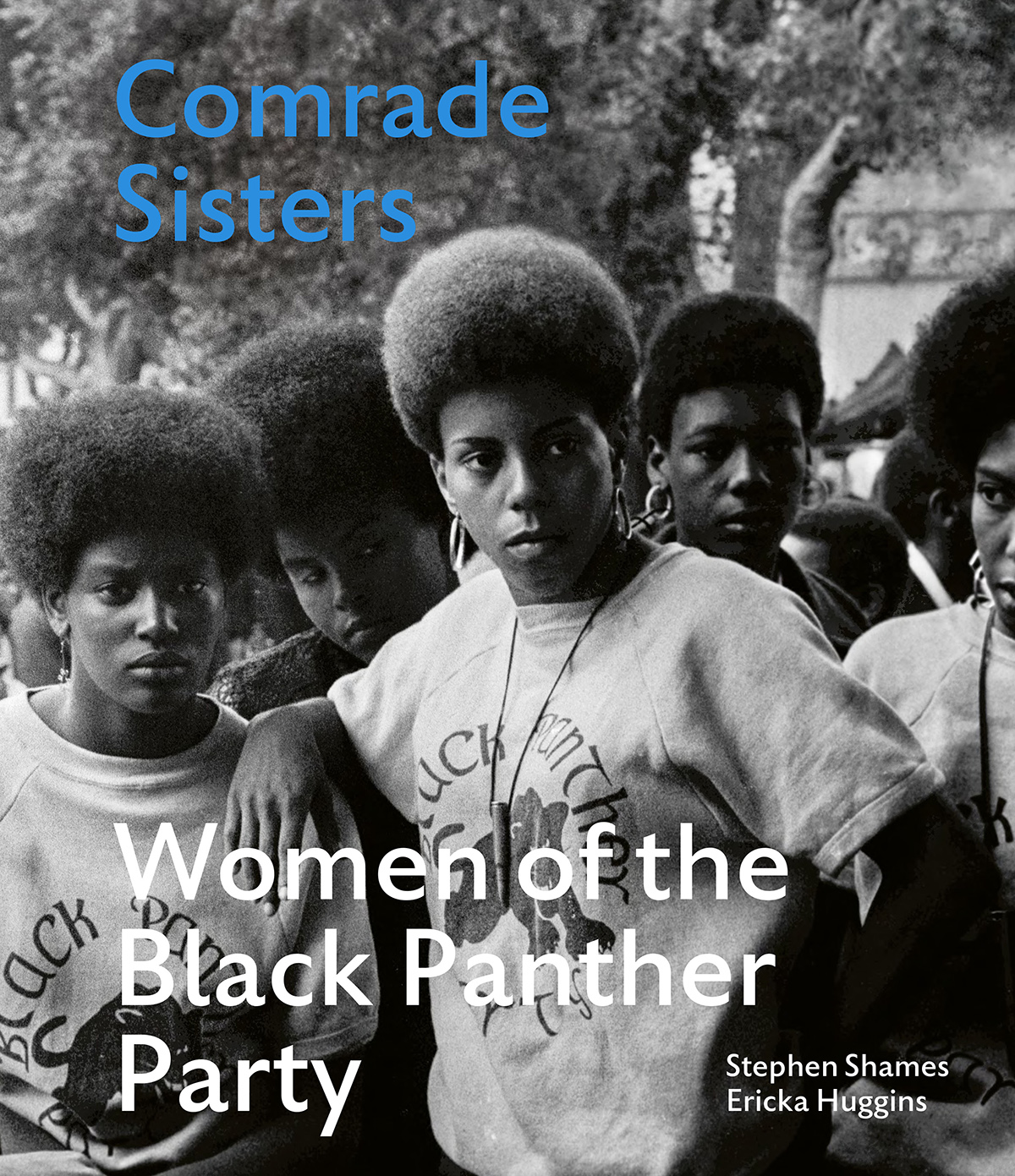

The historic Black Panther Party, originally the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, is one of the most spoken about organizations of the civil rights movements, remembered even decades after its founding in 1966. Speaker, writer, educator, and former leader of the party Ericka Huggins dedicated much of her life to the party and continues to educate the public on the true story behind the Black Panthers. Huggins is now shining a light on the women of the party with her forthcoming book, Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party, co-authored by award-winning photojournalist Stephen Shames. It is notably the first book to tell the stories of the women who were the true backbone of the movement and the pivotal work they did to promote justice through many of the party’s lesser-known projects, all through the eyes of historic photographs taken by Shames.

Huggins sat down with Indira Cesarine, Editor-in-Chief of The Untitled Magazine, to share insights on the forthcoming book releasing this October, as well as personal accounts of her time joining the movement and as a leader of the party. For 14 years, Huggins worked for the Black Panthers, first on their newspaper and later as a school director, serving her community based on an ethos that is unfortunately still present today: the desire for justice for the marginalized. In 2022, she is proud to continue that work with Comrade Sisters.

With a preface written by Angela Davis, the book additionally features contributions from over 50 former women members of the Black Panthers and their families. With Comrade Sisters, Huggins brings many of those hitherto unrecognized actions back to light, and hopes to highlight the legacy of the Black Panthers and the global influence they had, sharing many never-before-seen photographs of their female members doing the work they cared about most for their community. In celebration of the release, she will be touring the book throughout the US, hosting events at Stanford University, the Museum of the African Diaspora, the Schomburg Center, and the Oakland Museum of California, among others.

Read the full interview with Ericka Huggins by Indira Cesarine below.

You joined the Black Panther Party in 1967 when you were only 18 years old. Can you share what motivated you to join at such a young age?

When I was 15, I went to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. I went by myself, and that day, listening and watching, I made a promise to myself to serve people for the rest of my life. I didn’t know how that promise would [manifest] itself over time, but once I was a college student, it became clearer to me that there was something I was supposed to do with people younger and older than myself, and that wherever I went in the United States, the conditions of poverty were the same for African American people. At that time, the African American communities weren’t as culturally rich as they are now; they were just Black communities separated from white communities. I also knew though, that wherever there were people of color, wherever they were from, they were treated differently from white people or European Americans – we can use any term you like; “different,” “less than.”

And I saw this as a child growing up in Washington, D.C. It isn’t like somebody taught me this. I could see it with my own eyes and hear it as people shouted horrible things. So when I got to Lincoln University – a historical Black university, by the way, one of three that opened during the enslavement of African people. I’m assuming you know why there had to be Black universities.

There was a lot of segregation and separation – it wasn’t an integrated culture…

No, and sometimes, people don’t know why. They think it’s us separating from something. No.

I’m sitting there, and someone brought me a magazine that was kind of tattered because it had been passed around among the students. It was a feature article in Ramparts; I think it had to be early 1967. The feature article was about the Black Panther Party. In that article was a photograph of Huey Newton strapped to a hospital gurney under police watch. I kept reading the article and looking at the photograph. The photograph was familiar to me from the arrests and harm and jailing of people for no reason in my neighborhood in D.C. – not the D.C. that we know about in the news, the real Washington D.C. So, at that time, reading that article, I thought, “This is what I’m supposed to do.” This article says that the Black Panther Party – its original name was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense – is for all poor and oppressed people, and I thought, “I love this. This is bigger than just Black communities; this may be a way of ending the war in Vietnam. This may be a way of looking at the conditions of, at the time, Latin American people, Asian people, indigenous people, because the land is not ours, really. It’s unseated territory.”

I’m sitting there thinking, and my friend at the time, who later became my husband, John Huggins, walked into the student union building where I was sitting on the Lincoln campus. I really didn’t have words to describe how I was feeling, so I just passed him the magazine, and he read it, and I said, “You know John, I want to leave school and drive across the country to California and free Huey,” because there was a big defense committee for his freedom for being wrongly accused and incarcerated. We both wanted to do the same thing, and we did. We left Lincoln. I was in my junior year, and we drove across the country in his little car with a friend. All we had was gas money; we didn’t have a clue. When you’re young like that, you just go for it. We didn’t have a clue where we’d stay, or how we would get work, or whether we’d even find the party, but we did. And we joined, and for 14 years, that was my life.

Of course, you may know by now that John was murdered in an orchestrated event by the Federal Bureau of Investigations’ Counterintelligence Program. When he was 23 in 1969, he was assassinated on the UCLA campus with my friend Alprentice Carter. I continued on, and I want to say that there were times when I thought I couldn’t continue without John. He was, not only by that time of his death, my husband, but the father of our little girl. She was three weeks old when he was killed.

That was why and how we joined. We didn’t come with any particular idea of what we would do; we just joined. We did everything. That’s actually all we were asked: “Can you cook a meal? Can you wash dishes? Can you sell the party’s newspaper? Can you speak to people? Can you take care of the people?” and we said, “Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, and yes.” That was it. There wasn’t some long–and–involved anything.

It was based on true belief and passion for making a difference.

Yes, exactly. We all have that in common. That’s the beauty of the book for me: The common bond. We all were drawn to the party for the same reasons. And before that – there have always been movements that called for some portion of freedom. From not wanting to be enslaved and revolting, to all of the wonderful movements of young people today. And so, this book is, “That was then, and this is now.” They’re similar, I’m sorry to say.

I understand. There’s also a tie-in with what’s happening today with the Black Lives Matter movement. There’s obviously been a resurgence in the importance of parties like the Black Panthers, and the precedent they set with the work that they did. Even today, there are still several misconceptions about the Black Panther Party, one of which is that the party was violent because they chose to exercise their right to bear arms. Another common one is the idea that it was an extremely male-dominated group that championed masculinity and viewed women as subordinate. Can you address some of these misconceptions for our readers so they can learn a bit more about the history of the party?

I just want to say first, my assumption about the magazine when I went online to look at it was that young women were either driving it, or it was focused on gaining the attention of young women. I work with young people intentionally because I hold dear to my heart those years when I was young. I don’t look back at it in regret. The young people who are waymakers and change agents, they’re culture keepers. Also, to use the big definition of culture, they are the ones who not only want things to shift among humans, but they are the ones willing to step out.

I just want to say that I really love that Angela Davis agreed to do the forward for this book, and Alicia Garza the afterward, because it is exactly where we all are right now in shifting our misconceptions and misunderstandings and our fear of one another. I really love that Mahatma Gandhi said at one point, and I’m paraphrasing, “When we think we see hatred, it’s really fear at the core of it.” And it’s true. As I think about all the hateful things that I know about in our world today – and there are lots of them – underneath, I know that fear is driving it.

About violence – the persons who hold that awareness, yes, they’re misinformed, but also, they have been taught not to consider the violence of this country. I can’t think of one more violent thing and violating thing than setting up an economy based on owning humans; based on creating territorial rights by stealing land and killing indigenous people. That is violence. Our desire to stop the knocking down of our doors and the random shooting and beating of us – I watched this as a child. My sister and I watched this as [children] walking to the corner store in Southeast Washington, D.C. We saw a police officer jump out of a car and grab a random Black man. That’s one of my earliest memories of what we’re talking about today. He had nothing in his hands, not even grocery bags – he had nothing. He wasn’t wobbling as if he was drunk or intoxicated. He was just walking down East Capitol Street, and we yelled because we didn’t have an idea of the violence of the police at that time. We were just little girls that saw something really wrong. And what happened was, in the houses behind us, people started coming out of their doors, and the police jumped back in their cars and sped away. The abuse of power is violence, as we are seeing today with the hearings on January 6th. We’ve even nicknamed it. It has a whole place in history because of the violent abuse of power. No one has the right to own a human. I can’t think of anything more violent.

The descendants of enslaved people said, “No, young ones. You can’t continue to do this. We will defend ourselves.” And the idea of defending ourselves struck some nerve in the white American psyche – the guilt, and the shame, and the fear of retaliation. We were just saying, “You cannot keep killing us like this.” We never voluntarily went out and harmed people.

I remember that my mother told me – and Angela Davis tells a similar story when asked about violence – I remember my mother telling me she grew up in North Carolina; one of 11 children. It was not the modern South. She was born in 1918, and she said when she got old enough to understand what was going on in her world, she’d go to church. They went to church every Sunday, and the pastor would walk down the aisle, and he’d have two things: His Bible and his gun. Why do you think? Just any idea, Indira, that you might have about why he might have those two items in his hand?

There’s a component of self-protection. He obviously had fear of living through the day.

And his congregation. Protecting his congregation. Why is that considered violence? Even Martin Luther King, when asked about riots, talked about – and again, I’m paraphrasing – he talked about the necessity to physically protest against wrongdoing. He didn’t believe that nonviolence was just turning the other cheek. He was powerful and led his people in that way. It goes back to a very powerful Gandhian understanding of Ahima: No harm. So, there was a way that the Black Panther Party felt similarly. We didn’t want any more harm to come to our people, and so we thought, “We will state it loud and clear.” At the time, people had the right to bear arms. We’re not talking about the random mass-murder kinds of things that are going on now.

And let’s look at that. Why are young white men so violent right now? It makes me sad when I look at the news and I see they were 18 or 19 years old. They killed people, and then killed themselves or were killed by law enforcement. That’s really sad. That says something about our society. That doesn’t say much about them. They believed that they were going to live a life of quality because they were white and male. The other piece of it is, perhaps, that they were poor, and no one ever told them that that wasn’t a privilege that made a difference, so they take it out. It makes sense to me, and it’s so sad when I think about it. I feel a similar way about the mothers that lose their sons and daughters to police violence. That really is violent because there are places in the world where police are not allowed to carry weapons.

Of course. In England and many other places, it’s not common.

And we build the most prisons and jails of any country in the world. So, violence – I hope it’s making sense to you how we looked at it, and how I look at it now. I want to be able to say, if someone comes to harm one of my grandchildren, that I will defend them. I might even put myself out of the picture to defend them. That was how we felt.

In regards to the women in the party – the focus of the book – often, people have perceived the Black Panthers as a male-dominated group, although I know that shifted and they became more than two-thirds women party members as time evolved. Can you talk about the importance of women in the party?

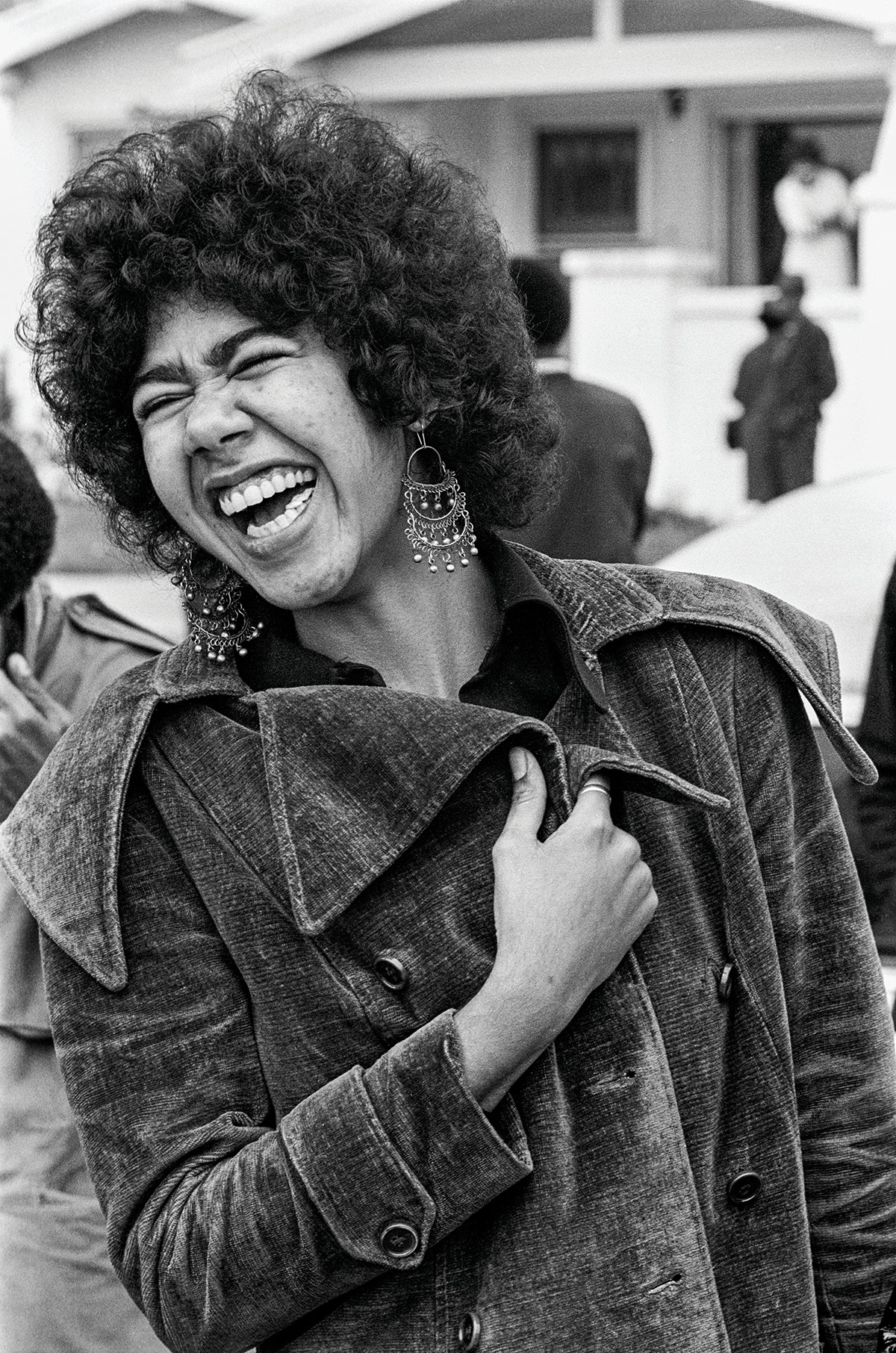

And the importance of women everywhere. That’s what I mean, and I mean it seriously, the importance of women everywhere, at every table, especially decision-making ones. Because we tend not to go toward the principles of war. That doesn’t mean there’s nothing stronger or more fierce than a mom. Sometimes, moms are like lionesses. They will go to any length to protect their children. It defies any rational thing you can come to; it’s built-in. These young women, all of them – the ones we know, and all of these women that we don’t know in this book that we’re getting to know through this book, that we are getting to know through Stephen Shames’ beautiful photographs from decades ago – they are important models for how to be and how not to be in our world. So, speaking about women in the Black Panther Party is speaking about women in the world. What do we do? Well, we create a magazine that serves women. Young ones.

Someone tells us, like Bobby and Huey, co-founders of the party, “We want to develop community survival programs.” We had this sort of a phrase because the need is survival pending revolution. It’s an abolitionist principle. The abolition of all prisons. But wait, there are people in them – millions of people in them. We can’t ignore them as we say we want to abolish prisons. The women took the 64 different community survival programs and not only coordinated them but sustained them. The sustenance of life is something that women tend to do. I’m not saying men don’t, I would never put men in a silo, but since women had been in a silo, women of the Black Panther Party said, “I can do anything you can do.” We called ourselves revolutionaries. If we want to make a 360-degree change, then men, you’re going to have to think it through.

My understanding is that, by 1969, the Black Panthers adopted a sort of anti-sexist policy where there had to be gender equality in the party. That was way ahead of its time, which was really interesting.

And why don’t we know it? Why is there all this misinformation? ‘Cause I’m sorry if this is hurtful to anybody’s ears or eyes when they read it; we live in a society where the dominant culture is white and male. For a really long time, if we think of the first wave of feminism, white women were not only just arm candy, but were actually, in certain countries, owned on paper by their husbands. And their children, as well. Like cattle. But they weren’t “slaves,” it was just the property, which is not all right. Why? Because there’s this need for power. I don’t know that it’s part of all-male humanity. That’s a ridiculous statement to try to make. But I do know, culturally, this was handed forward, reproduced, decade after decade, century after century. The trickle-down was Black women and other women of color weren’t even human, so how could they be women? And why would we concern ourselves with them? It was the dominant culture. It’s those men who will have to subdue. That was part of it.

So then, Angela Davis, Kathleen Cleaver, Elaine Brown, and sometimes myself, we were not famous. We were infamous. That’s why we know about them. Dominant culture said, “Oh, look at these Negros. Look at these uppity Black women.” I’m being polite; those were not the terms used. Angela was stalked. Elaine was castigated. Kathleen was stalked. And I haven’t talked about my story because this book is not about me. I’m honored to be the co-author though, helping to put together the women’s words that they spoke to me in Zooms like this one.

That’s so cool. I was wondering how you put it together with over 50 women of the party. You did it through Zoom.

It was just a conversation, and then, we got their permission to do outtakes of the conversation so they would fit because the conversations were hours long. Some of us hadn’t seen each other in 30 years. It was like a reunion and lots of fun. And it was poignant. Sometimes we were just bowled over in laughter, and sometimes we cried. But then, the outtakes became something that I turned over to the ACC art books – to the editor, a young English woman, who said every time she read the stories, she would cry.

It’s a very powerful book. Looking at the photos, the programs that the Black Panther Party were doing for the community really stood out. Can you talk about some of the community outreach programs? You had medical programs, the prison busing program, the breakfast program – There were so many powerful community programs that you guys were doing!

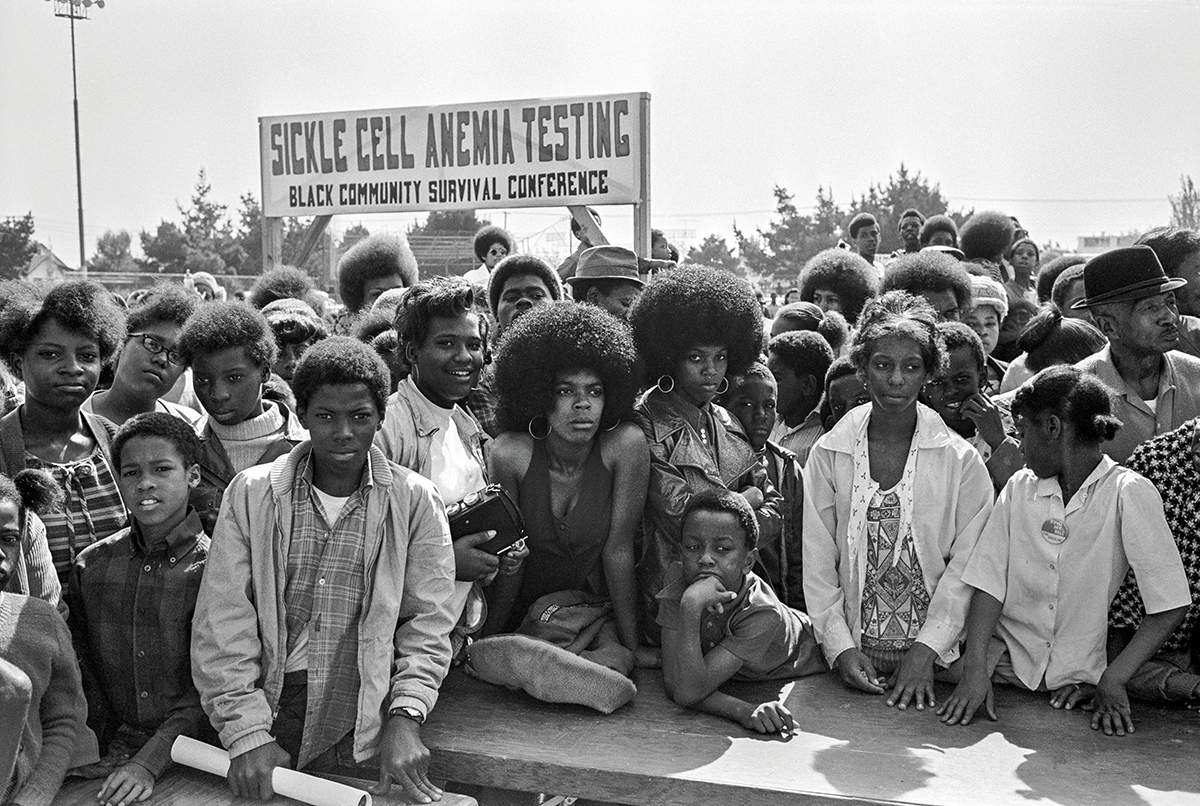

And that was why the government was coming after us. J. Edgar Hoover, who was, for 47 years, the head of the FBI and the originator of COINTELPRO, said, “It’s not their talk about self-defense that threatens us. It’s those breakfast programs.” What was he saying, though? Think about it. Think like him for just a second. The people loved us. We were feeding their babies before they went to school because the government wasn’t. We listened when they said, “The doctors don’t understand sickle cell anemia. They say it’s a Black disease. We tell them we have something really wrong. We’re in pain, and they say, ‘No, it’s pernicious anemia.’” We heard them, and we went to our doctor friends and our scholars of medicine and nurses and so on, and said, “Tell us more about sickle cell.” And we were told there wasn’t very much research or education about it, but literally, the blood cell is sickle-shaped, and it’s common to Black and Mediterranean peoples. The doctors weren’t educated about it. So we, in our people’s free medical clinics, decided to go out with little folding tables on the corners – and you can see it in the photos in the book – and do pinpricks and test people for sickle cell. And we helped to start one of the first sickle cell research and education programs. Now, the whole government does it.

The same with the breakfast program. As a result of the breakfast program, the federal government was so embarrassed that they created the National Free Breakfast and Lunch Program. Fine! All we ask is that the children get fed and that the people get treated in a healthy manner.

We started the very first free ambulance program in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. When people think of a city to go to, do they think Winston-Salem, North Carolina? No, they don’t. There are so many wonderful women in Winston-Salem, but Hazel Mack stands out to me, and she and four or five women write about this in the book. Not only did they start the idea for the free ambulance program, but they also educated the community by doing it.

See, we listened to people. That was the key to every single one of those 64 programs. People said, “It’s cold in Chicago and New York, and we need free winter coats and boot programs.” So we started the free clothing program. Kids couldn’t go to school if they didn’t have a winter coat, but can you buy a winter coat if you are living in conditions of poverty? No. These are things that people don’t think about because they don’t have to think about them.

This was so frightening to the government that the attorney general in 1969 said, “We will wipe out the Black Panther Party by any means necessary.” John Mitchell and J. Edgar Hoover said we were the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States. And they did a good job; they did what they set out to do.

Back to the community survival programs – the sustainers of these programs, like Hazel Mack, not only helped start the free ambulance program in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, but I believe the NAACP heard about it and helped them buy an ambulance. That’s a lot of money at any point in history. And seven of them went to a local college program to become EMTs. They weren’t asking other people to take care of it. The Black Panther Party saw the needs of people and met them as best we could. We didn’t have any money. We didn’t have any financial resources like that, but we made it happen. We made it happen. All of these programs were created to be easily replicable anywhere, in any culture. People speaking any language could have a breakfast program. And as I have traveled in my life, I’ve seen all over the world that people have taken this. Right here in Oakland, California, where I live, they’ve taken these principles of the free food program. You saw the beautiful spread of grocery bags with women filling the bags with groceries. We gave out 10,000 bags of groceries in one day. I look back on it, and I go, “How did we do that?”

Where did they get the resources for the food?

Big box stores, like Safeway, as an example, and others. We also collected food from smaller stores that donated to us. What I loved most was, toward the end of that 10,000 bags of groceries, Bobby Seale said, “We want a chicken in every bag.” So we figured out how to do it. We thought, “What? Thousands of bags with a real chicken in it?” And we got them. We went to locations that were famous for raising and putting chickens into supermarkets and asked for a donation of chickens. I mean, we were just creative. We had fierce imaginations, and we loved people. The bottom line is that we made it happen.

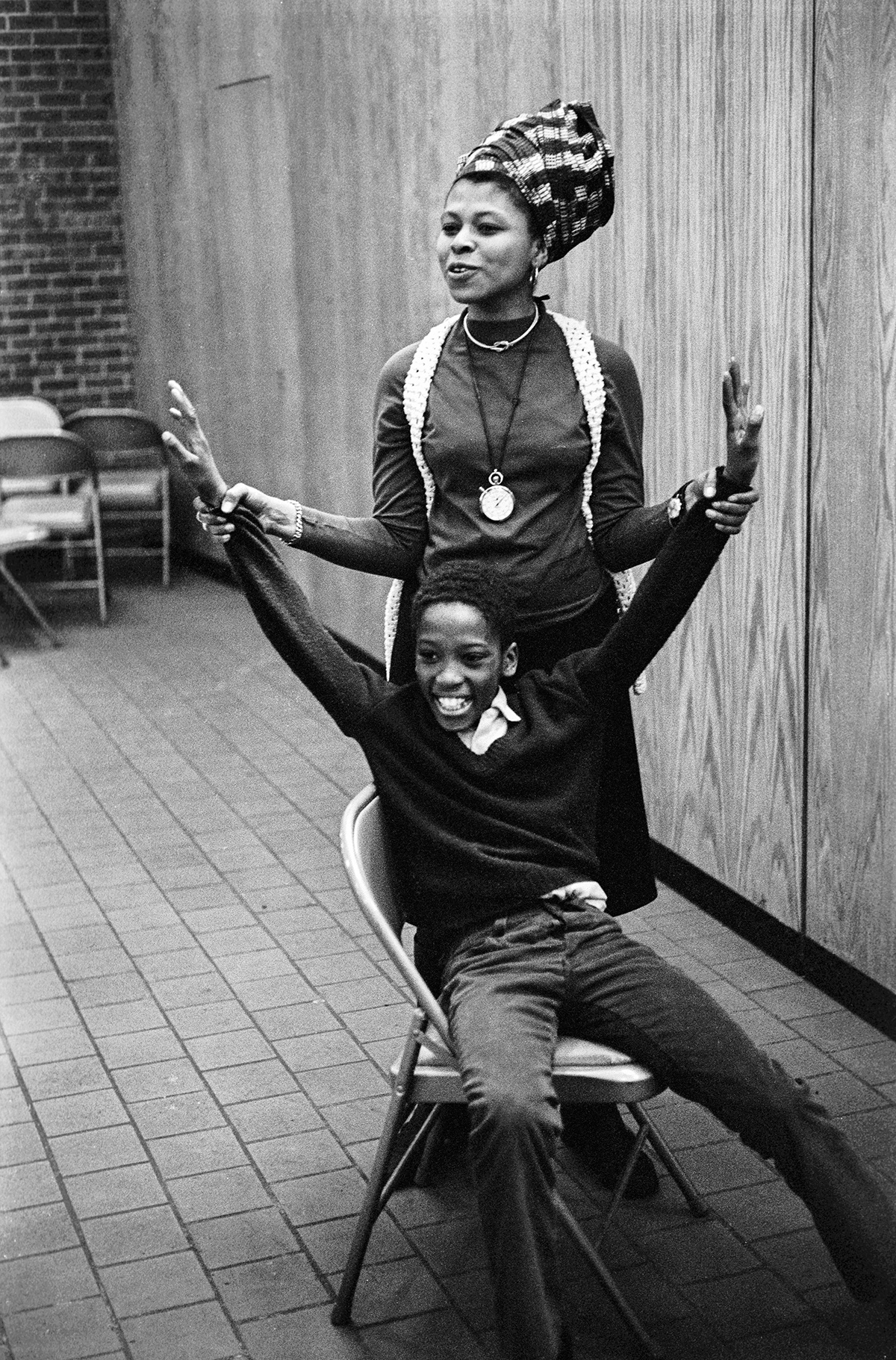

The other thing that really struck me in the book was a lot of the photographs of the children of the party where you can see groups of them with their little berets and in classrooms, and it was pretty phenomenal. I understand there was a huge emphasis on education, and seeing those photographs of the children is really incredible and moving. Can you talk about that?

Yes, and I do want to say that, since the photographs are Stephen Shames’ photographs from the thousands of wonderful photographs that he took – he stopped taking photographs in 1973 – but I want to let you know that, in 1972, we decided to move from the school you see in the photographs of Stephen’s to a bigger one. We’d outgrown the place where we were, and we created something called the Oakland Community School. At the Oakland Community School, the children weren’t in uniforms of any kind. And we got better at it, and it lasted for 10 years. Yes, we were very strong about education because, in our communities, education was historically kept from us.

There is a myth Black people don’t want to be educated. They don’t want to learn. Their parents don’t care. These are all myths. During slavery, people learned to read in English while knowing they could be killed, or that their tongues, or hands, or fingers could be cut off. They did it anyway. [I don’t think] it is necessary to go back to the times of enslavement and stay there very long because it’s so sad, but to know that time is a continuum, and we were the ones moving things forward. There could have been more humans like John Brown who wanted it to move forward from the perspective of those in power, but we did the heavy lifting. The schools, both of them, were modeled on the old church schools in the South, and in the North where, because we couldn’t go to school with white children, the aunties and the grandmothers and the mothers opened the church basement and created a school. You can track those schools back to the 1920s, actually.

That was some of what we did, and we were also very young. For Oakland Community School – once the Intercommunal Youth Institute that is pictured in the book – there was a shift from that, and we got larger. The staff sat and decided, “What was it that we needed when we were children? Because we want to give whatever that is to these children.” It was three meals a day because mothers were working two or three jobs, and fathers as well. It’s less to worry about, and the community trusted us. We wanted to have an arrangement with the local children’s hospital, and we did. Whether you had insurance or not, whether you had cash in hand or not, we made an arrangement so that our children could be well-cared for, and then the financial part of it could get worked out.

What were your specific responsibilities? I know you were one of the leaders of the Black Panther Party. Did you have specific responsibilities, or were you one of the people that, since you started at such a young age, were involved in all aspects?

I wasn’t involved in all aspects, and I never thought of myself as a leader because I don’t really know what that means. In my house, I take the lead on watering the garden. Does that make me a leader? I don’t know. To answer your question really specifically: At first, I worked with the Black Panther Party newspaper from, let’s say, 1971 to ’73, and then, I was asked to be the director of the Oakland Community School. I was already working with the party newspaper when I started working with the school that you see in the pictures, and I loved it because my daughter and my son were there by that time. And then, when we shifted to Oakland Community School, I was asked to be the director, and that is what I did for nine years; I was in the party for 14 years. I was also, sometimes, a spokesperson for the party, like when Fred Hampton was killed in Chicago. I traveled to Chicago to speak at a very public memorial for him. That’s an old example of what I was doing, but I also spoke about the party’s educational programs regularly and became part of a very wonderful association. It was called the Association of Alternative Schools. Our community school, we didn’t consider it to be just an alternative to public school. It was a model for what could be done even by a public school teacher in his or her own classroom. I loved that organization, and really famous educators who were not known then came through that association, like Jonathan Kozol and Robert Cole. The most amazing part of my life at that time was working with children in that place, and that’s something I had always wanted to do.

What do you think drew so many women to the party?

Serving the community. That’s it, period. Seeing a need, recognizing that the party was trying to meet the need, and stepping forward and becoming a part of it.

There’s a lot of talk about Angela Davis, who is obviously – still – a very famous party member. Were you close with Angela? I know she wrote the preface of the book.

She’s my friend. She will be my friend forever. When she was incarcerated, I was incarcerated. We wrote letters to each other. She is my friend now, and she is one of the kindest and most compassionate, and brave women I’ve ever met. The reason why we know her is that she has continued to serve nonstop. I’ll tell you what she says about herself, and I love it, and I use it too because it’s true: “People talk about me as an icon, but I am one of many.” This book could have been called One of Many. That is how we felt. That’s how we felt in the party. That’s how we felt in the ensuing movements. That is how Alicia [Garza] and Opal [Tometi] and Patrisse [Cullors] felt when they sat together in tears and coined the term “Black Lives Matter.” They weren’t thinking about what would happen and governmental pushback. They were thinking, “Our lives matter.” Three women; three queer women. Three of many. There’s this idea that, if you’re in the public, you must have done something wrong or something right. But it was unheard of before the Black Panther Party for young Black men and women to stand up in the way that we did.

With this book shedding so much light on the intimate stories and history of the party, how would you like the Black Panther Party to be remembered?

For its legacy, for its love of community, and for what it left for us. I’m telling you, every time I travel – I was in São Paulo, Brazil working with students, and the student organizers had invited people from the nearby favela. We call them ghettos or barrios here. This young student who was taking care of an elderly person with disabilities raised his hand – I spoke very little Portuguese, and he spoke very little English, but we had a translator, thank goodness. I didn’t want to force him to have to say what he wanted to say in English. Ugh, English is not the universal language – Brazilian Portuguese, by the way, just as a side note, is so beautiful.

Anyway, he had this big smile on his face, and he said, “Someone gave me an old party newspaper. Don’t know where it came from. It was well-used,” and we all laughed. This was only a few years ago; I was no longer young in years. I’m listening intently, and he said, “In my favela, the elders and the children suffer from lack of food. So I saw the ‘Free Food Program’ in the party newspaper, and I did it.” He was about to say how he did it, but there were 300 students there – and Brazilian culture is so physical; so alive – and the students began stomping their feet. They gave him a standing ovation. They were clapping; they were singing. There were people crying that he did that. That is the legacy of the Black Panther Party – that anywhere, you can do what is necessary. And it’s not against the law; I know that COINTELPRO tried to pretend we were against the law for starting breakfast programs, but it’s ridiculous.

That’s one story. The other story, which is in the book, is the story of the Polynesian Panthers, the Fiji and Samoan and Tongan women and men who were sight unseen – never met one of us. They were in Auckland, New Zealand in 1970. They started something called the Polynesian Panthers, and Uncle Will – that’s his name – is spoken about in stories from the women in the book or their sons and daughters. Uncle Will said, “Just read Bobby Seale’s book, Seize the Time, and understand their community survival programs, and we’ll just do what we can do.” They never talked to anybody. They never met anybody. They just knew it made sense. The first thing they did was put in a stoplight in a very busy residential area in the poor community in Auckland. Why? Because pedestrians were being killed routinely, so that was the first thing they did. Then they did prison work, working directly in the prisons and supporting incarcerated men and women and getting them help. They did food programs, and they did health programs.

So, when we thought about this book, we thought, “We can’t do this without them. We’ve got to meet some of them in the year of the 50th anniversary of the party,” which, I believe, was 2016. We reached out, and some of our Zooms were from California to Auckland, New Zealand, and it was so amazing. There was no difference between the needs that they spoke about and the needs here.

Amazing! Thank you so much for sharing all this with me. I’m really excited to hear that you’re having your book tour coming up this fall. I can’t wait to share the story behind Comrade Sisters with our readers.

Yes, we’ll be at NYU, at Columbia University, at Greenlight Bookstore, at the Schomburg Center in Harlem, and two other places, all in a condensed amount of time starting the 24th of October, so make sure to mark your calendars!

Interview by Indira Cesarine for The Untitled Magazine

To read our print feature on Ericka Huggins, pick up your copy of “The REBEL Issue” here.