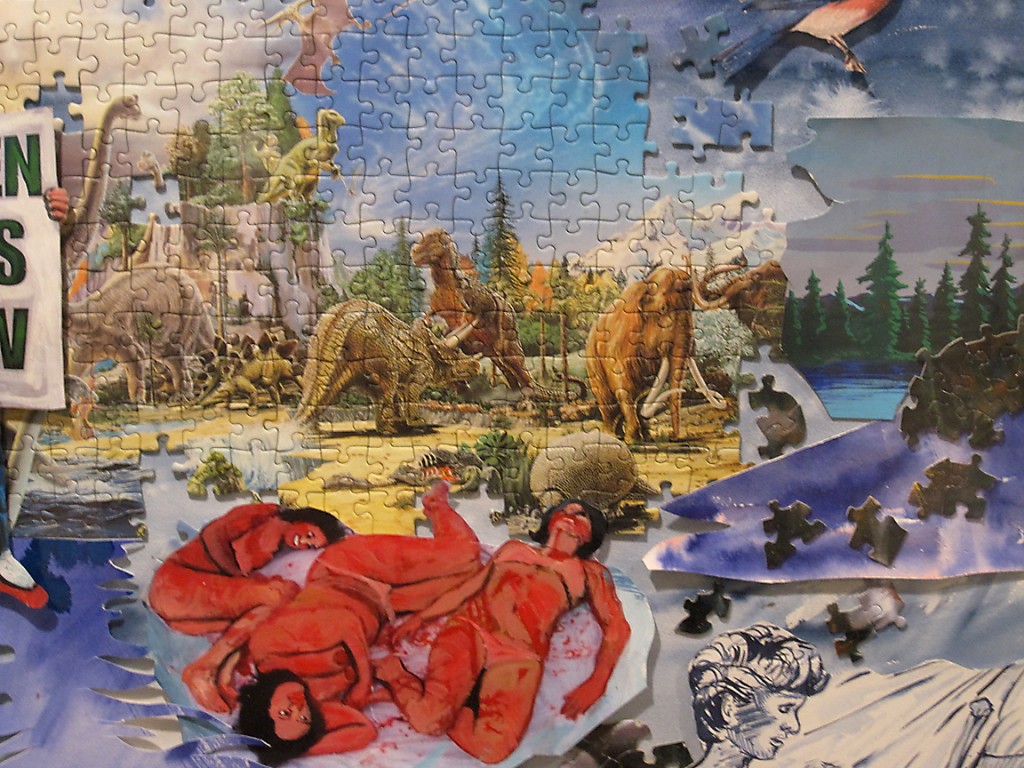

An image from Magarita Gluzberg’s “Avenue des Gobelins” exhibit

An image from Magarita Gluzberg’s “Avenue des Gobelins” exhibit

Paradise Row

The London art scene is talking about Paradise Row, the latest gallery to move to the artsy hub of, none other than, the West End. Founded by art critic Nick Hackworth in 2006, the gallery was named after a road in Bethnal Green where the inaugural exhibit, “Welcome to Paradise” took place. In 2010 they moved from their previous occupancy on Hereford Street in Shoreditch to settle in a high-end location on Newman Street where the spotlight shines brighter on the galleries’ long-standing, London-based group of artists, Shezad Dawood, Diann Bauer, Margarita Gluzberg, Douglas White and Eloise Fornieles. The move coincided with Hackworth’s desire to ‘get more people to see the work…it was getting increasingly difficult to get people to the East End.’ In forming a strong alliance with this group of artists, Paradise Row’s ambition is to engage with the ‘general and fundamental themes that culture has historically dealt with, displaying an interest in aesthetics and a willingness to engage with the poetic as well as the critical and the political.’

Over the past few years, Paradise Row has risen to the ranks of one of the most cosmopolitan, diverse and influential contemporary art galleries in London. Contemporary art followers thrive on the way in which it deals with a variety of contemporary concerns through the lens of the five returning artists. Since its tactical move, the gallery has attracted an avid new audience without losing its long-standing regulars. Seemingly overlapping with its move is Paradise Row’s increasing interest in politically focused exhibits and perhaps the adoption of a more serious, intellectually complex standpoint.

Recent exhibits held by the gallery include a group show entitled ‘The Pavement and the Beach’ which showcased the work of twenty-three artists between July and August 2011. Defining a historical moment in time, the protests that took place in ’68, the emblematic phrase, Sous les pavés, la plage – ‘Beneath the pavement, the beach’ acted as the starting point for the exhibition’s creative standpoint. On one side, the exhibition critiqued a society so exhaustingly contingent upon the manufactured world of power, efficiency, subjugation, work, consumerism and regulated thought, symbolically represented as the pavement. On the other, the exhibition’s ‘beach’ stood for the opposing utopian world of radical leisure, freedom and imagination.

The task set up for the artists was to attempt to regain notion of freedom in their work by providing a critique of the causes of its loss. As the exhibition’s description pointed out, ‘The sphere of leisure and entertainment has become an arena in which power insidiously dreams itself into new disciplinary forms.’ Whether engaging with the phrase directly or with a symbolic approach, the exploration of perceptions of capitalism lodged itself in the forefront of the exhibitions aims.

Some highlights of the exhibit included the iconic image of Queen Elizabeth II’s head present in Finch’s piece ‘Constellations 3,’ as well as the ransacked supermarket shelves photographed in Jean-Michel’s piece ‘Super #1.’ Bold slogans present in Guillaume Paris’ ‘Kids’ and Steven Le Priol’s ‘Yes We Can’, stood out as forthright propagandist works with a critical message against the exhibition’s metaphorical ‘pavements.’

An earlier exhibition in the year marked the inaugural European show of work by Iranian artist, Hesam Rahmanian. Presenting a body of works which responded, with a mordant and mournful wit, to the repression and violence inflicted by the current theocratic regime in Iran on the country and its people. Rahmanian’s work pictured uprisings, riots and revolutions, which have taken place in the Middle East in spectacular forms. Choosing to refer to his subject matter as ‘Arab Springs’, Rahmanian used the free, imaginative space afforded by painting to construct visual collages, allegories and metaphors that provide an alternative critical response to that provided by documentary. Rahmanian’s fictive spaces allowed for the symbolic debasement and abuse of those in power. Fluid, gestural and painterly, Rahmanian’s style manifests the spontaneous energy of popular discontent.

In a similar vein, dealing with political challenges and events through art, Paradise Row showcased exhibitions at the start of this year by Diann Bauer entitled, ‘The Enemy is Everything That Might Happen.’ Prior to this year, Paradise Row focused on the exploration of less politically charged exhibits including an installation show by Eloise Fornieles which toyed with the concept of ‘creating a series of spaces that co-exist at once, physical and aesthetic, psychological and emotional, that amount to an expanded portrait of the human body.’

Magarita Gluzberg’s “Avenue des Gobelins” opened on November 17th. While it’s less obviously political, it still concerns itself with power relationships, articulated through the lens of desire and the economics of consumerism. The painter and illustrator presented a stunning series which presented photographs and slide projected imagery with a fashion aesthetic. The exhibit included a series of classically framed prints which seemed to channel early Man Ray with their tonality and subject matter, as well as a series of several slide projections on graphite. Her work mixes themes of consumer culture with reflections in windows, shadowy portraits and fashion iconography, creating timeless and somewhat glamorous images.

The following quote, “Everywhere I go I dress up and I go out I got lots of gwalla, let me show you how I show out Everywhere I go I dress up and I go out I got lots of gwalla, let me show you how I show out Gucci, Louie, Prada, man I’m all about my dollas I be all up in the mall ballin like it’s no tomorrow Gucci, Louie, Prada, man I’m all about my dollas I be all up in the mall ballin like it’s no tomorrow” is featured on the website about the show that borrowed its title from one of Eugene Atget’s iconic 19th century photographs of Parisian shop fronts. “”Avenue des Gobelins” is a meditation on the mystical, ritual nature of material desire and consumption… It is the black gleaming lacquer of Chanel, reconfigured by the chaos of a Saturday afternoon at Primark…In Gluzberg’s hands, the camera becomes the interface between the consumer-voyeur, and the constantly changing, spectacular display of commodities. She creates images that seem to echo an age when consumer fictions were being invented for the first time, and brings them back to the present, a present where such fictions are becoming increasingly unsustainable.”

We met up with gallery director Nick Hackworth to talk about the gallery’s premise and some of the recent exhibits that have been titillating the art world.

IC: What do you think defines Paradise Row as a gallery?

NH: A gallery is defined by the artists in their stable. A common thread that runs through the work of our artists is their conceptual and intellectual rigour and that, though this is something of a generalisation, we represent artists that are fundamentally interested in the world, rather than limiting their interest to the internal concerns of art.

IC: So you’re saying that many artists make art about art?

NK: A lot of artists make work that only makes sense within a web of references that you can only understand if you’re steeping in the culture and history of contemporary art. That work has its value and place but I’m interested in artists that make work that basically speaks to concerns that culture has always had… the existential problem of existence, morality, suffering, war, love, beauty… these kinds of very fundamental topics which always come. That’s what I think distinguishes the artists at Paradise Row, an irrepressible desire to intelligently interrogate the world.

IC: I’ve noticed that quite a few of the artists have a political point of view, which I see more at Paradise Row than many other galleries.

NH:Well a lot of contemporary artists deal with politics but that’s a reflection of what I was talking about.

IC: …that they interrogate the world?

NH: An interest in the world the world does not obviously necessarily mean one has to be political, it can be manifested in the aesthetic or all sorts of things

IC: but I have noticed a distinct political thread running through your curatorship.

NH: it’s alongside an interest in the poetic.I’m very interested in artists who engage with poetic alongside the political. These are not words that I think are often used in the art world anymore because these are phases with a little bit anathema. The art world is still very much dominated by the legacy of modernism, and then more recently the legacy of conceptual art of the sixties and seventies, and there’s a style and an ethos that goes with that, that runs counter to the aesthetic and is suspicious of beauty or the romantic but I see the poetic and the political are kind of two sides of the same coin really, they stem from an engagement with the world, an interest in human relations and how that constitutes it. I am a (unclear) political art, but I am also very skeptical and pessimistic about the ability of political art to actually change anything.

IC: Your background came from journalism. You were working at the Evening Standard as an art critic and as an art editor at Dazed & Confused. Can you tell me a little bit about your transition into being a gallery owner and curator?

NH: I was a Contemporary Art Critic for the Evening Standard, for about six years and founded Paradise Row in 2006. The transition was pretty easy because basically I represent a number of artists; the core of the artists that I show are people that I’ve known, some of them since I was quite young; I went to school with them, I went to university with them, I kind of wrote about their work for years and I kind of even, with many of them, got involved in the making process like helping them out, being there during photo shoots or whatever, so just after six years of being a critic I was a bit frustrated just writing about them. I’m naturally quite commercial and I enjoy promoting people so running a gallery was like the perfect combination of everything because you still have a political voice. The nicest thing is that I’ve had some creative conversations with some these artists for over the last decade, from being a critic to being a gallerist. But these conversations have been going on for over ten years. It’s amazing to part of that process and to be on this journey with them.

IC: What do you think of merging of fashion and art? There are a lot of people in the art world that have a reflex action when they hear the word “Fashion”. They’re like “oh my god forget it I’m not interested”. They think Retail. They immediately think it is commercialisation, with a lack of soul, and tend to rather poo-poo the fashion world as superficial. Do you think that Fashion and Art can in any way shape, reform, collaborate with one another and compliment each other?

NH: I think these are two questions there; one of them is about the relationship between art and commerce and then the second one is more specific about the relation between art and fashion. Between art and fashion I think anyone who polices those category distinctions too closely I think is probably just insecure or a little bit worried, I think good creative work, in whatever field it emerges, is interesting and cross-cultural collaborations open up all sorts of possibilities. But I think probably people are likely to worried when we’re talking about big businesses with large amounts of money getting involved with artists.

IC: So what’s the difference between sponsorship and branding? Because loads of artists have sponsorship and corporate commissions.

NH: There’s not necessarily a problem I think it’s a case-by-case basis. Artists have their brand and in a sense it is actually a branding issue, if you want to look at it cynically.

IC: Art is retail, galleries sell artists work as a commodity, a product.

NH: Yes but it might be very simply that an artist can easily undermine their own brand by being too involved with other brands. However if it’s done well and tastefully, and for example a fashion brand picks up a creative talent and wants to work with them to do say, video art, that crosses the border between marketing and art, I see absolutely no problem with that but I think it’s up to each individual artist to make sure that they produce something that’s really still quality work and means something as well. And also isn’t ashamed to act in tat kind of commercial aspect. Equally, the worst thing is to pretend it is something that it isn’t. If you take someone’s money you’re part of their marketing process and I think you should at least be very explicit about that. So essentially, in principle I don’t think there’s any issue at all I think it’s really just issued case by case. Part sensitive to the brands and on the other side how the artists deal with each particular commission.

IC: Can you tell me a little bit about some of the artists that you have recently exhibited?

NH: Right now in London we have Douglas White. In November we show an artist called Margarita Gluzberg, who is Russian born and moved to the U.K when she was ten. And we are doing a show called “Avenue Des Gobelins” and that draws on a series of photographs that Eugene Atget who was a pioneer photographer about a century ago in Paris, a series of photographs he took of basically of emerging consumer culture. The photographs are of fashion shops, arcades, window displays. This was kind of like, a really crucial time when consumer culture has been developed. He took these very dream-like photographs of these fashion stores. Margarita is making a co-work which she called “Consumistic”; a configuration of the words Consumer and Mistic. The work is almost hallucinatory, confused,a look at the rituals of desire and consumption. What she’s done is made a series of projected slide and video works, using films that she’s put through the camera like three, four times so she’s going to add some shots; window displays, the architecture of consumer environment, images from marketing and advertising, and what you get of these amazing over-load images where you have the ghostly face, maybe of a model, or of some kind of advertising display and that face is floating in some kind of consumer display with the clothes, with the shoppers. It’s almost like high fashion and modernist architecture reconfigured through the chaos of Primark on a Sunday afternoon. She’s got all those things together, and we’re displaying these using slide projections, video and these very beautiful platinum prints she’s printing. What is fascinating about her work is that she’s interested in economics and how the world of economics, which seems to us so rational, you know, if you go to the economics section or the finance or business section in the newspaper it’s facts and figures; the world pretends that this is an arena that is logical. In reality all these things are basically driven by desire, you know it’s like a libidinal economy that Gluzberg came up with, so that’s what her work is about.

IC: That reminds me of Andy Warhol, he did window displays as well. That was his first career before he was really an artist.

NH: Yes he did all those advertising and illustrations for magazine; really delicate illustrations.

IC: Yes, although it seems Gluzberg presents a different point of view, as more of an objective, outsider looking at the consumer culture and creating a poetic critique of it. I heard you also opened a new gallery in Germany?

NH: You know we opened a new space in Dusledorph, Germany in September, and this German space is showing Adam Broomburg and Oliver Chanarin; they’re two photographers who have been working together for over fifteen years. South Africans based in London. They’re fascinating because they’ve been disengaging from the position of documentary photography for five or six years now; they kind of lost faith in the medium. So all their work since basically almost questioning what photography is and how it works; what images mean, how we conceive them, how they circulate and operate. They are doing a show called “Poor Monuments”, and it’s based on a book that Bertolt Brecht published in1955 for the War Primer, and Brecht basically took a series of images named it “Conflict In War”, and he published these as photo-epigrams; the book is 85 pages of images of Nazi Germany from the Death Camps, Hiroshima, from all the fronts, from the home fronts as well. What is interesting is about how images manipulate us, how people use it, how power uses images as propaganda, and what he wanted his book to be, hence the word “Primer”. It is almost like an education on how to read an image, or how to pull it apart. They physically bought 100 copies of Brecht’s original work and they created “War Primer 2”, and they super-imposed literally just using printing and sticking on top a contemporary image for every single image of the Forties and Fiftees that Brecht used; an image that will carry the same sense. So there’s one image that is an arial shot of a city being bombed from very high up. it was probably taken by one of the bombing planes, and it has a wonderful line in it something like “these were sons of fire they came out of the light” etc and the have super-imposed a 9/11 image on top of that and they went through the entire book doing that. The point being is that obviously these images are portrayed exactly the same way; essentially nothing has changed.