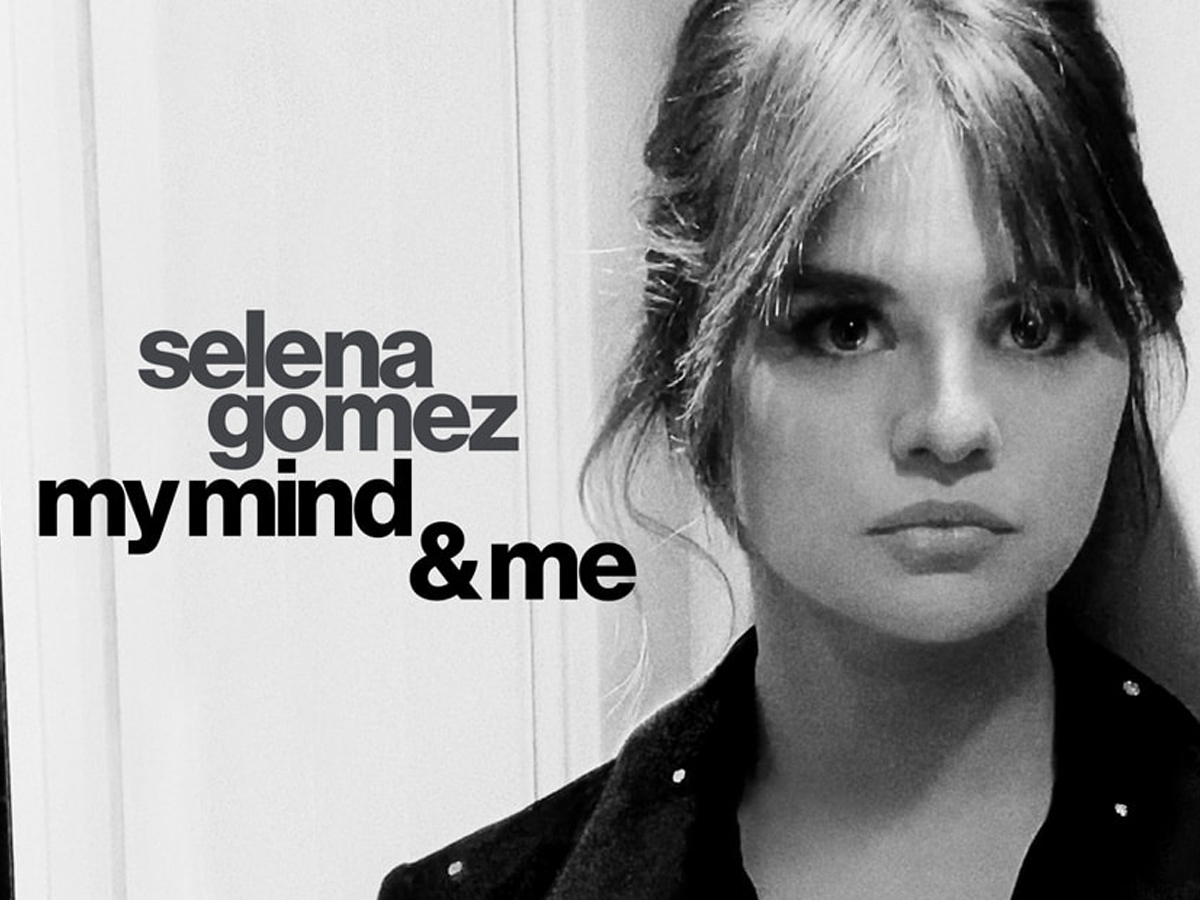

Apple TV’s documentary directed by Alex Keshishian, Selena Gomez: My Mind & Me, was released on November 2nd, pulling back the curtain of stardom to reveal the truth of Gomez’s struggles with lupus, depression, anxiety, and bipolar. The film follows Gomez from 2016 onward, presenting a raw, sometimes ugly, sometimes depressing, but always honest and undeniably moving portrait of fame and mental illness.

The film opens in 2016 at the LA Sports Arena with Gomez preparing for her Revival tour. She worries after her final rehearsal that the entire show is a disaster–that her body does not look womanly enough on the screen, that she’s missing moments she needs to capture during the performance, that she’s tripping over the costumes, that she’ll never leave the “Disney kid” of her past behind. In a powerful moment, clips of a performance of “Who Says,” her 2011 song about self-love, are juxtaposed with her backstage struggles. Her team works to reassure her, to build her up, but the efforts do not penetrate her consciousness and the pressure builds until a psychotic episode where it is revealed that Gomez has been hearing voices and wanting to die. The documentary cuts suddenly to The Revival Tour being canceled after 55 performances and Selena being hospitalized for psychiatric treatment, an experience that is not part of the documentary itself.

Some may claim that not showing years of struggles is disappointing, but the fact is that Gomez has the right to have her personal struggles off-camera and is brave to be showing as much as she is and as openly as she is. We see Gomez at many humanizing moments where one would not want the cameras rolling–annoyed with an interviewer who does not ask the right questions, or talking about how difficult her day-to-day life feels, or how much lupus hurts. She shares, as she promises at the beginning, her deep dark secrets with us. The documentary makes us privy to so much of Gomez’s internal journey that it would be a mistake devoid of empathy to criticize it for not opening her up entirely.

The story is not one about her “passing relationship” with Justin Bieber, which the paparazzi repeatedly grill her about against her will, nor is it about promotion for her upcoming career–it’s about her relationship with herself. During particularly emotional moments, the film brings in sequences from Gomez’s diary, opening with the lines “I have to stop living like this. Why have I become so far from the light?” set to dark, expressive movements from Gomez in the background. “Everything I’ve ever wished for–I’ve had and done all of it. But it has killed me,” she says. More diary entry scenes are set to Gomez taking a bath in rose petals as she wonders how she can learn to breathe again when she is so depressed. The effect is artsy and intimate, taking the viewer out of Gomez’s reactions and affect from the outside to her internal monologue.

The film pulls in Gomez’s past in the form of old home videos and visits to haunts and people from her youth. She visits old neighbors and her old high school, where she was a shy girl with 2-3 friends who kept to herself, sometimes ate lunch alone, and went on “vacations” from her real life to act–her first booking being “Barney and Friends” at the age of ten. By visiting these past facets of herself, Gomez is putting back together an identity that was defined for her early on by the roles she had to play. She is finding herself all over again.

Eventually, the thesis of the film–Gomez’s search for meaning and internal peace–takes her to Kenya, where she raised money for the WeCharity, which is later revealed to be embroiled in controversy itself. During these moments, we learn from Gomez why she does what she does even though “it has killed” her–she wants to use her platform to make a difference through philanthropy and advocacy for mental health.

Her outlook on mental health shows a degree of internal resilience the viewer would never wish upon anyone, as she concludes that everything she has been through has been to be able to relate to and help people with the same problems. The sense of purpose she displays–an antithesis of the way depression wears down one’s personality–is used to fuel her continued management of emotions and progress in her career, even through hard moments where the depression feels like it is winning. The film is not the PR-pushing machine that many popstar documentaries are–it is the truth, even when the truth is difficult, not glamorous.