In Season 4’s ‘Redux’ episode of Homeland the audience was privy to yet another of Carrie Mathison’s episodes. We watched as she slipped into the familiar spiral that transformed her from a sharp, determined woman, into a paranoid, debilitated mess, slave to her emotional turbulence. This season has not been easy on Carrie, who has grappled with various moments of moral misconduct. First we watched in horror as she contemplated infanticide with her baby daughter. We were later transported to Pakistan, where Carrie used experimental tactics to win the trust of her barely legal asset. As she slipped into lingerie and under the sheets with a boy who was on the tale end of puberty – ignoring the fact that she was responsible for the death of his entire family – we were forced to question whether Carrie had at last become completely unhinged.

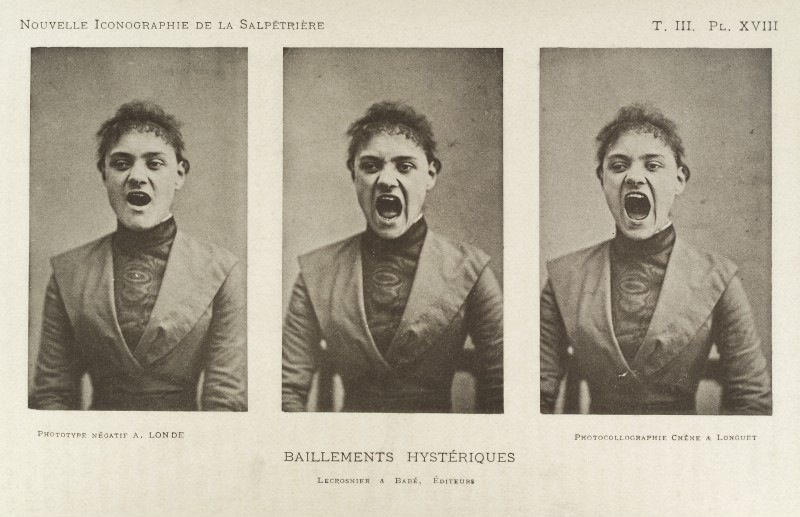

We have reached a point in television and media where we are seeing a growing number of powerful leading ladies, often occupying major territories in politics, law enforcement, and beyond. However, there is a consistent issue with the portrayal of many of these women, who are falling victim to one of the most pervasive and dangerous tropes of our society. Throughout history women have been depicted as overly emotional, crazed – ruled by their hysteria. This stereotype has been used to oppress women, to limit their reach, both in fiction and in reality. Until recently, female hysteria was a real medical diagnosis that covered a whole spectrum of issues, ranging from anxiety to mood swings, and immoral behavior. Despite eventually being eradicated from the medical vocabulary in the 1980s, this concept of the crazed, hysterical woman has prevailed, and it remains alarmingly apparent in media today.

Carrie is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to female characters whose emotional outbursts are their kryptonite. The media has set up a world in which emotions are a sure sign of weakness, and any outward display lands you squarely in the crazy corner. Take Detective Sarah Linden of AMC’s The Killing; clearly brilliant, determined, and fiercely independent, yet continuously subject to crippling emotional outbursts that leave her puffy faced and alone – marked as unstable. Even the elegant and poised Olivia Pope, leading lady of ABC Family’s Scandal. Sharp-tongued and quick-witted, she is still, despite her extreme rationale and unwavering moral compass, ruled by her inability to defy her lust for the president. While it is important for a believable character to have flaws, these women seem to be anchored in the stereotype of the hysterical woman. Their flaws are not unique, unexpected challenges, but rather, a perpetuation of a threatening cliché that continues to define how we view women in today’s society.

Associating emotional responses as a female weakness is not only damaging for our perception of women, but also has serious implications for expectations surrounding men. The media creates these unrealistic ideals that continue to influence how men and women behave in the real world. We have Don Draper of Mad Men: smart, serious, stoic, completely unfaithful and a terrible father, yet glorified. His flaws only solidify his character, making him all the more desirable to both men and women. It is figures like Don Draper that are setting the standard for what we expect men to be; serious, professional, disconnected from emotion. Through our prevailing acceptance of Draper, we are condoning similar behavior in men of our society. If we can turn a blind eye to all of Draper’s bad behavior, why should it be any different for regular men? Despite his propensity to find solace in the beds of women who are not his wife, or to lash out at his team of loyal creatives, we forgive Don. And by not holding him accountable, we are accepting this behavior in all men.

What is more, male characters that toe the line of crazy do not receive the same negative reception as female characters. Walter White of AMC’s Breaking Bad is a prime example of this gender bias. White is unlikeable, detestable. He is mad and driven by his ego, yet his craziness is branded as brilliance. He is a genius, and that overshadows the fact that he regularly commits atrocious crimes. These male characters, though apparently flawed, are perceived as complex and fallible, whereas their female counterparts are often branded as crazy, irrational, neglectful, or any number of narrow definitions that manage to limit women from reaching their full potential, both as characters and in life.

Perhaps it is because we have not been given the language to understand women as complex characters in the same way that we have been for men. The media paints them as “crazy”, and as an audience, we accept them as such. This extends out of television and into the broader media. Women who are outspoken about their feelings, or show any outward display of emotion quickly become poster girls for the hysterical woman. Britney Spears’ emotional collapse was keenly observed and documented by every major publication. Taylor Swift has been pinned as the psycho ex-girlfriend so frequently that the whole world watches her relationships, anxiously awaiting the inevitable breakup and subsequent emotional downfall. We are fed a vocabulary for understanding these characters, and too often it veers towards crazy, hysterical, emotional, unstable.

Despite the consistent portrayals of the hysterical woman propagated by the media, we are beginning to see a wave of women challenge this image. Taylor Swift is one of a slew of women in media who have taken it upon themselves to dismantle the notion of the “hysterical woman.” She has not shied from addressing her reputation, and recently drew attention to the absurdity of this archaic stereotype in her music video for “Blank Space.” In the video she confronts the stereotypical behavior associated with the crazy ex-girlfriend, challenging viewers to question the title Swift has previously been branded with.

Orange Is The New Black presents a cast of women who deliver characters with a range and depth that consistently avoid the “hysterical” tropes seen in so much contemporary broadcasting. Even the signature crazy character, aptly called Crazy Eyes, is given an opportunity to explain her behavior. She is not simply another crazy woman, but a woman that has been through adoption, struggled with racial discrimination, and confronted her anger management issues. Hannah Horvath of HBO’s Girls offers insight into a character that strikes more than one note. She is selfish, brash, insecure, funny, a little bit obsessive compulsive, and most importantly, relatable. The overwhelming success of a show like Girls can be attributed to its unabashed honesty. It avoids entertaining repetitive tropes, and instead gives us imperfect, unpolished, and wholly real women who are struggling, just like everybody else.

This critique is not a new one, far from it. Many people have addressed the issues of how women are portrayed in media, particularly through the “hysterical woman” lens. Tina Fey wrote a segment in her book, Bossypants, discussing the implications of depicting women as crazy. She defined this woman as “a woman who keeps talking even after no one wants to fuck her anymore.” The “Overly Attached Girlfriend” meme sprung up a couple of years ago as a parody of the stereotype and was an immediate internet sensation. David Fincher’s recent thriller, Gone Girl, allowed the audience to interact with the “crazy girl” in a way that others have veered away from, providing insight into the complexities of the character, rather than brandishing her as crazy and leaving it at that.

Dismantling the “hysterical woman” has been on the feminist agenda since its inception, and has been an issue that is especially relevant to their cause. A quick google search on ‘hysterical woman and feminism’ yields a slew of results ranging from “Will the Feminists Ever Stop Their Incessant Bitching?” to “Women Against Feminism: Are These Bitches Crazy?” These results only further emphasise the point that women who are vocal in their beliefs are often castrated for it. ‘Feminism’ has become stigmatised, it is associated with the overly emotional, irrational, women-who-can’t-get-laid. These narrow descriptions are further indication of the influence media has on public perception. The message, simply put, is: Women who have opinions and are vocal about these opinions are crazy.

While we are seeing more coverage of the issue, little seems to be changing. We continue to get different versions of the hysterical woman, as evidenced by the ‘Redux’ episode of Homeland. These portrayals have a greater impact on our society than people seem to be aware of. They continue to influence how women are perceived, often dictating how women should act and placing restrictions on certain behavior that is otherwise appropriate for men. Women who are succeeding in their fields seem to be at the greatest risk of negative stereotypes. The “crazy” label is so readily used to diminish a woman’s achievements. Taylor Swift may be the most successful female musical artist of our generation, but people continue to recognize her as the “crazy girl” who writes songs about her breakups. Never mind the fact that Hillary Clinton might be the first female President of the United States, and instead the focus is on how the smallest sign of emotion is an indication of weakness. For these amazing, accomplished women, their successes are dwarfed by the reputations built from tired tropes.

The greatest evidence of the ubiquity of this unfortunate stereotype lies in women’s tendency to label other women as “crazy.” Any disagreeable behavior, anything that irritates or angers, often results in the brandishing of the “crazy” card. This attitude discourages women to be outspoken or to step outside the line of conformity. While this trope has deep roots in history and we are constantly battling to dismantle damaging social opinions of all kinds, the media has done little to help this cause and more to harm it. The media plays a key role in influencing how people view women; it has the power to rouse change and inspire action. Despite this, it seems to propagate the oppression of women. The hysterical woman trope seems too easy, a lazy alternative to creating real, complex characters. It’s time we see a few more real women on our screens. It’s time we abandon the hysterical woman.

– Article by Minka Bleakley for The Untitled Magazine